"If I had my school..." It's a thought that crosses the mind of many dedicated teachers but rarely materializes beyond wishful thinking. However, for one former IER graduate from Dhaka University, this daydream transformed into an educational empire that spans multiple cities in Bangladesh's northern regions.

"Wali Bhai, you don't know that what I'm doing today is inspired by you," the man told Waliullah Bhuiyan, founder of Teachers Time, during a chance encounter at a university where he now serves as public relations director. Years earlier, this same individual had participated in seven different training programs offered by Teachers Time, a teacher and educator development initiative under Wali's company Light of Hope Ltd.

"At that time, I was just working a job; I never thought of becoming an education entrepreneur," he explained. "But after your training, I got so motivated."

What followed was remarkable by any standard. He went back to all the educational theories and practices he studied during graduation. He established his first school in his hometown of Rangpur, which grew to serve two thousand students. Success bred ambition—he opened a second school in Rangpur, then expanded to neighboring Thakurgaon with two more schools. The ripple effects continued as he adapted Teachers Time training modules to create professional development programs for his school teachers.

"Now I go to different district schools and conduct training," he told Wali. "I've trained in seventy schools regularly. My schools now have two hundred full-time teachers, all well-trained, and thousands of children are studying."

These are the moments that Wali treasures most—evidence that Teachers Time, the teacher-training initiative he founded under his company Light of Hope, is fulfilling its ambitious mission to transform education in Bangladesh by cultivating educational leadership where it matters most.

In a country where the teaching profession struggles for status and career advancement, Teachers Time, an initiative by Light of Hope, has been quietly revolutionizing teacher development across Bangladesh since 2017, training over 100,000 parents and teachers in the process. Its mission is deceptively simple but potentially transformative: to create education leaders, one teacher at a time.

The brainchild of educator and entrepreneur Waliullah Bhuiyan, Teachers Time emerged from a first-principles analysis of Bangladesh's educational landscape. "We wanted to see if we could bring fundamental changes to primary-level education in Bangladesh," explains Wali. "We thought, if we invest in education, where should we invest to get the highest return on investment in terms of impact?" Wali recalls thinking when his team began planning what would become Teachers Time.

Their analysis led them to focus on two critical intervention areas. First, improving children's reading skills by establishing school libraries. Second, and perhaps more consequentially, providing quality training to teachers.

The focus on teachers was pragmatic. The logic was straightforward but consequential. In Bangladesh, a developing nation, the highest societal returns come from investing in primary education, whereas in developed countries like the United States, the greatest returns come from tertiary education. Within the primary education system, well-trained and motivated teachers emerged as a powerful leverage point for change. Yet the quality of teachers entering the profession was declining, with limited career advancement possibilities beyond becoming a school coordinator or principal.

However, Wali's vision extended beyond traditional classroom instructors. "When we named it 'Teachers Time, why did we choose that?" he muses. "If you're training parents, why call it 'Teachers Time'? Because we believe that the best teachers for children are not just school teachers but also parents." From the beginning, the initiative encompassed both professional educators and parents, recognizing that education begins at home.

Teachers Time began modestly with in-person workshops charging 500 taka (about $4.50) per session. Wali was uncertain if anyone would come. In Bangladesh, teacher training was typically provided free by the government or NGOs. The idea that teachers would pay for professional development seemed far-fetched.

"We didn't believe people would come," Wali admits. But they did come, revealing an unmet demand for practical, high-quality professional development among educators. Thus initial skepticism about teachers' willingness to pay for professional development quickly dissipated as educators from both private and government schools began attending in growing numbers.

As attendance grew, the organization began to understand the topics teachers were most interested in and the challenges they faced daily in classrooms. Private schools, the Teachers Time team discovered, often had no budget for teacher training, creating a significant gap that Teachers Time could fill.

The initiative evolved organically. First came in-person workshops at the Light of Hope office. Then, responding to demand, the team began conducting on-site training sessions at schools. By 2018, recognizing the limitations of face-to-face instruction in reaching Bangladesh's million-plus teachers, the company began recording courses based on its most popular workshop topics.

"We realized we had to scale this whole thing," Wali explains. "There are ten lakh teachers in Bangladesh; how long would it take to reach them all?"

In mid-2018, Teachers Time launched an online platform offering eight to ten recorded courses. Some were free; others cost around five hundred taka. A significant breakthrough came a year later when the company signed an agreement with "Muktopath," a government e-learning platform catering to public school teachers.

This partnership allowed government school teachers to access Teachers Time courses at a reduced rate, receiving certificates jointly issued by Light of Hope and A2I, a government innovation program. The revenue-sharing arrangement benefited both parties while dramatically expanding the initiative's reach.

When COVID-19 hit Bangladesh in early 2020, forcing schools to close, Teachers Time made another shift. Within a month, the company had launched weekly one-hour live sessions for parents and teachers, featuring top educational experts in interactive Q&A formats. These sessions were recorded and made available on its platform for asynchronous viewing.

The pandemic accelerated the organization's digital transformation. Certificate courses moved online, including a popular early childhood development program in partnership with ICHD, a prominent Bangladeshi organization.

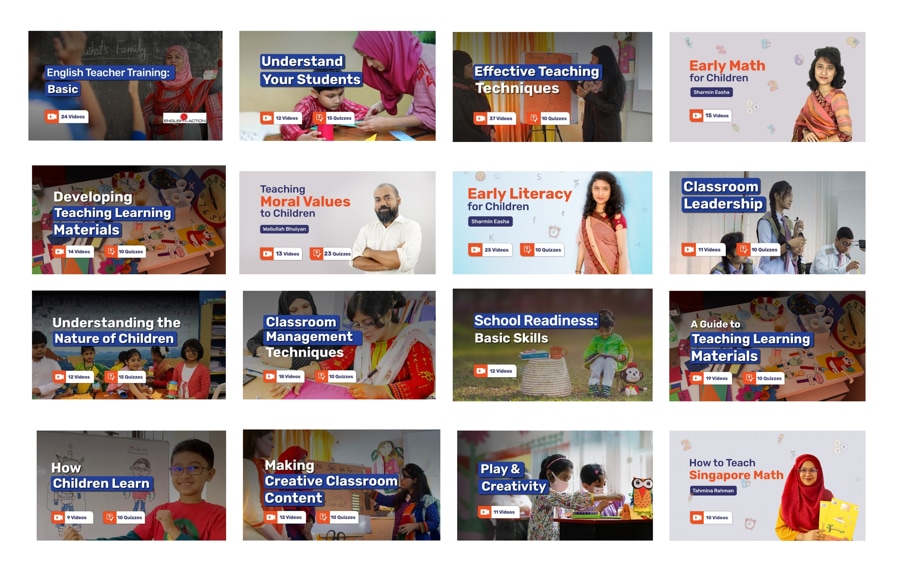

Today, Teachers Time offers approximately 25-30 different products through its platform. For teachers, these include courses on preschool teaching, early mathematics, language development, classroom management, and school leadership.

The curriculum is designed to support educators at every career stage—from novice teachers just entering the profession to experienced educators looking to advance to coordinator or principal roles. Leadership courses for principals focus on school morale and administrative responsibilities.

"We're creating a career advancement path for teachers," Wali explains, "from those who want to become teachers to those who want to grow in their careers."

The platform extends beyond classroom pedagogy to include courses for parents, recognizing their role as children's first teachers. "In many cases, the first teachers of children are actually the parents, and probably the most influential teachers in their lives are their parents," says Wali.

For parents, courses on early childhood development have proven particularly popular, attracting not only mothers and fathers but professionals from other fields interested in education.

More recently, Teachers Time has expanded into youth skills training, including caregiver, sales, communication, customer care, etc. to tackle graduate youth unemployment. The organization has also responded to post-pandemic challenges by developing courses addressing autism, speech delays, and smartphone addiction among children—issues that have become more prevalent in what Wali calls the "COVID generation" born in 2020-2021.

The educational formats are equally diverse: self-paced recorded courses, structured certificate programs running one to two months with four to eight classes, and live workshops lasting two to two and a half hours.

Throughout, Teachers Time strives to balance theoretical knowledge with practical application—a philosophy that has resonated with over one hundred thousand parents and teachers who have participated in their programs.

Currently, individuals, professionals, schools and NGOs - all are taking the courses offered by Teachers Time.

While Teachers Time doesn't systematically collect impact stories, compelling anecdotes emerge organically. Beyond the former Dhaka University student turned education entrepreneur, Wali cites another significant metric: of approximately one thousand mothers who completed their early childhood development course, more than two hundred fifty returned to the workforce as teachers.

"Some even went abroad and used the certificate to get jobs," Wali notes. These success stories have built credibility for Teachers Time among schools and principals, creating a virtuous cycle of trust and engagement.

This multiplier effect—where a single trained educator goes on to influence hundreds or thousands of others—represents the fulfillment of Teachers Time's mission.

Despite these achievements, Wali is not satisfied with the organization's overall progress.

He identifies several challenges. Finding qualified experts to lead programs has become more difficult since the pandemic ended, as potential instructors have returned to full-time employment. And the fundamental issue remains: teaching in Bangladesh is not structured as an attractive, long-term career with meaningful advancement opportunities.

"In private sector schools, the situation is worse," Wali explains. "A teacher's maximum dream is to become a coordinator or principal. However, most kindergarten school principals are the owners themselves. So, there's no career path for teachers. They're just doing a job, maybe some tuition on the side."

Even in government schools, teachers can rarely advance beyond school-level positions. These structural limitations make it difficult to attract the best and brightest to the profession.

"When I was young, in Cadet College, the quality of teachers we got in the eighties and nineties is nowhere near what we have now," Wali observes. "The quality of teachers is going down. Back then, job opportunities were scarce, and teaching was respected. Many thought differently about this career. Now, no one thinks of teaching as a career."

He recently advised government officials: "Make sure that the teachers you hire today as assistant teachers can at least become education officers, if not the education secretary. If you think the bureaucracy will block this, then at least let them become upazila or district education officers. If you can extend their career path to district or divisional levels, or even to the ministry level, then good people will join."

Faced with these systemic challenges, Teachers Time is refining its approach. Rather than attempting to train every teacher in every school—an impossible task given resource constraints—the company is now targeting influence nodes within the educational ecosystem.

"Always attract ten percent of teachers in a school, not more," Wali explains, drawing on a universal truth: in any school, a small number of exceptional educators have a disproportionate impact. "Think about your childhood: in school, you had ten teachers for ten subjects, but you liked one or two teachers. Maybe the math teacher or the Bangla teacher said something outside the syllabus that inspired you."

The organization's new goal is to place at least one Teachers Time graduate in each of Bangladesh's approximately one hundred thousand schools. "We don't need to train all teachers in all schools, but probably 10% of teachers in all schools should be our first target," Wali explains. "At least that way, we can ensure that in 1 lakh [100,000] schools, at least one teacher is a graduate of Teachers Time, inspiring children to dream, not just teaching well."

This strategy acknowledges the broader structural issues in Bangladesh's education system, where teaching lacks attractive career paths. Government school teachers cannot rise beyond certain administrative levels, while in private schools, most principals are school owners, creating limited advancement opportunities for teachers.

To support this vision, Teachers Time is creating a pool of master trainers from among their most dedicated graduates and collaborating with experienced trainers from both the government and private sectors.

In a country wrestling with educational quality challenges, Teachers Time represents a promising private-sector intervention. By focusing on creating not just better teachers but education leaders, it addresses a critical gap in Bangladesh's educational ecosystem. The true test will be whether these leaders can ultimately help transform an education system that currently struggles to attract and retain top talent in teaching.

Educational transformation is notoriously difficult to measure, with results often visible only years or decades after interventions. After five to seven years of operation, Teachers Time is just beginning to see the fruits of its labor in the form of individual success stories and shifting perceptions of teacher development.

A survey of Bangladeshi children under ten revealed that teaching ranks second only to medicine as their preferred future profession—a sign that despite systemic challenges, teachers remain influential role models for the next generation. This influence represents both an opportunity and a responsibility that Teachers Time takes seriously.

"From an engineering brain or first principle thinking, I think something good can be done," Wali reflects. "I can't change society or societal norms, but at least we can do something within that framework."

In a country where educational quality varies dramatically and teacher motivation often wanes in the face of limited career prospects, Teachers Time offers a modest but potentially transformative proposition: by investing in teachers' development and leadership potential, Bangladesh can nurture a generation of educators who will, in turn, inspire their students to dream beyond the limitations of their circumstances.

The two hundred fifty mothers who became teachers after completing a single course represent just one measure of this impact. The educator who established five schools and trains teachers across seventy institutions provides another. Together, they suggest that Teachers Time's quiet revolution in Bangladesh's classrooms may ultimately prove more significant than its founders initially imagined when they launched their first five-hundred-taka workshop in 2017.