In the past decade, Bangladesh has seen salient improvements in health care. We’ve significantly reduced child mortality rate and maternal death, and increased immunization coverage and life expectancy of citizens.

That said, there is a huge disparity in health care distribution between urban and rural areas, a large portion of people living in rural areas are deprived of modern health care facilities. The total population in Bangladesh is over 160 million (World Bank, 2018). Among them, 77% people live in rural areas. Access to medical personnel (general practitioners), medical facilities, and equipment is unevenly distributed throughout the country.

Two problems stand out:

Telemedicine service takes advantage of the developments in telecommunication and growing internet facilities to provide medical facilities in remote areas where modern health facilities are limited.

The idea isn’t new. In fact, telemedicine in Bangladesh emerged around 1999 when a telemedicine link was established by a charitable trust named Swinfen Charitable. Although it was a short-lived collaboration it planted the seed of an idea for remote treatment quite early. Over the years, many attempts at telemedicine have been taken.

In 2005, Grameen Telecom (GTC) in cooperation with the Diabetic Association of Bangladesh (DAB) launched telemedicine services, giving patients at Faridpur General Hospital access to specialist doctors of their choice in Dhaka. DAB’s BIRDEM Hospital Dhaka, was connected via a video conferencing link to DAB’s Faridpur General Hospital.

The initial results of the DAB Pilot Project were promising. In the first 3 months, there were 52 new patients and 6 returning patients. However, it never took off. The number of patients waned over the months. They had technical problems which made service delivery difficult. Another reason for failure is implementing the project in a city that’s quite near to Dhaka. It takes only 1.5-2 hours to travel between Dhaka and Faridpur by bus. Thus, the problem of access to physicians in the city may not have been as acute for Faridpur residents.

Mostafa et.al in a study stated as ‘Even though enthusiasm has been observed in deploying telemedicine in Bangladesh from different quarters, however, lack of sustainability and long-term deployments are major issues. Many pilot projects are not followed up to turn into stable and fully functional healthcare systems. The primary reason is that the projects started with a narrow scope and did not address a proper framework for telemedicine application in Bangladesh.’

The success of Telemedicine largely depends on effective communication during consultation in spite of differences in location, time, equipment, levels of expertise, and health care organizations involved in the exchange.

Challenges

According to Shammi Quddus, previously at health startup Jeeon, “As of today, telemedicine is a product for urban folks. For rural people the user experience is poor so that people don't come back. Also what you can solve is very limited. One can only prescribe OTC drugs, the video actually does not add any additional treatment abilities. In that way Grameen’s 789 is probably the most cost-efficient way to deliver the same outcome.

Where telemedicine adds huge value is for pre-existing doctor-patient relationships. Follow-up reports, regular check-in so that you are saving the time and cost of Dhaka traffic, getting your tests done and results back, and the doctor then actually has something valuable to opine on.”

Ahmed Bakr, from the current Jeeon team mentioned “With enough information, our doctors prescribed more than OTCs where necessary, especially in the dermatology cases. The key piece being: enough information such as pictures of past tests, reports, and prescriptions as well as current weight, BP, temp, etc. Getting all that information is challenging and time consuming”

These trends will likely continue for the next 5 years as local manufacturing of smartphones continues to drive down prices, mobile data gets cheaper and digital literacy continues to grow.

All of this is to say, internet services delivered via android smartphones are the best way to reach the average Bangladeshi today. This holds true in the context of telemedicine.

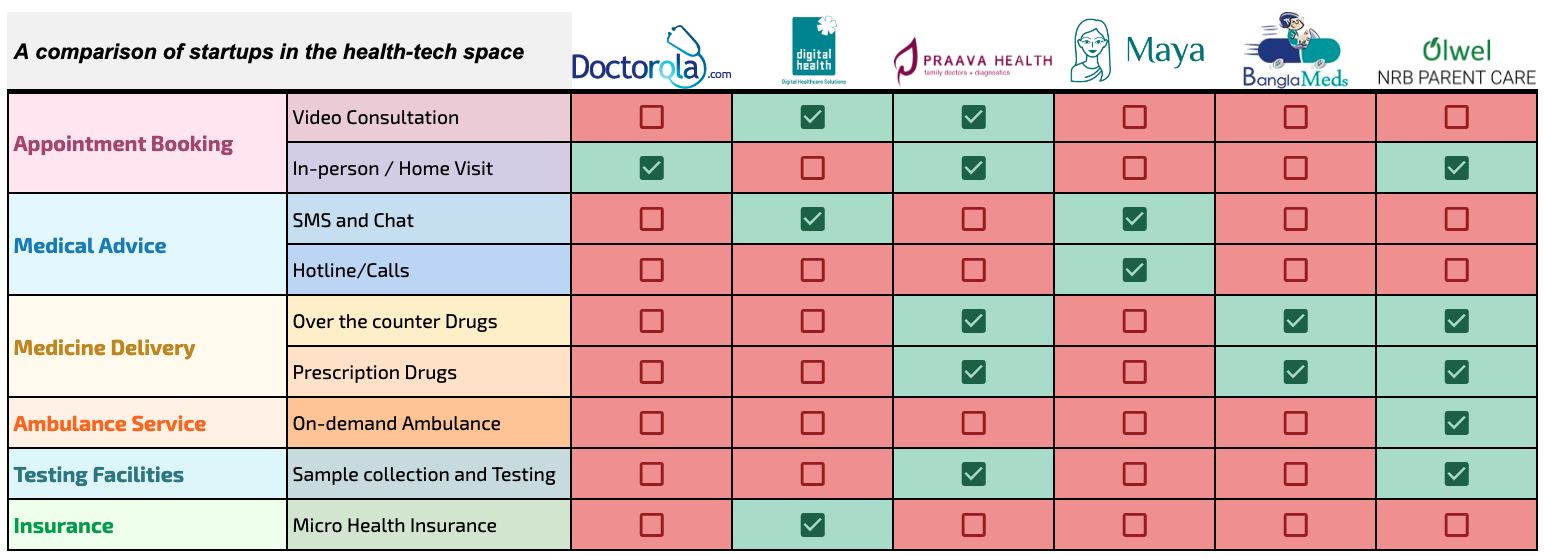

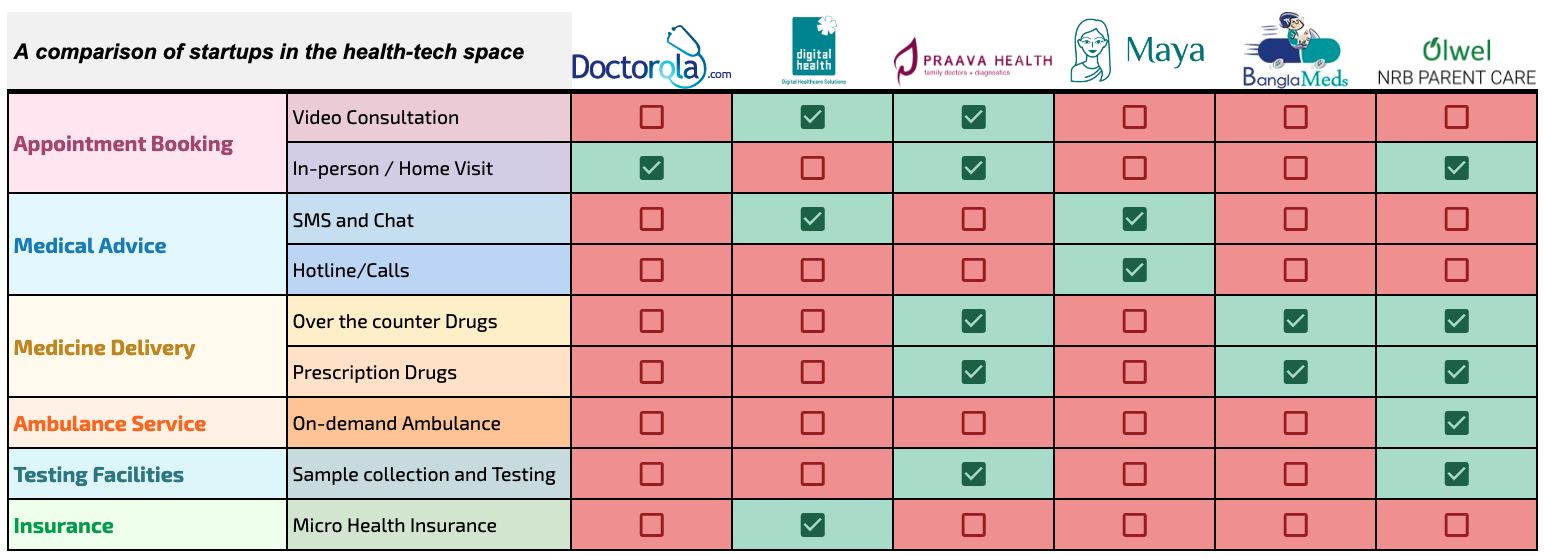

Here’s a comparison of startups in the health-tech space, as of May 2020:

These organizations have done well in developing a network of general practitioners and establishing reliable operations. Through increasing awareness about telemedicine and delivering reliable service each startup has received good traction. Although they carved out a niche for their services, their distribution and reach is limited.

There may be an opportunity to increase the awareness and adoption of these telemedicine and related services by featuring them in more widely distributed internet-enabled services.

Three options come to mind:

They have the customer information, the payments system in place and the balance sheet to take on this line of business.

Providing these value-added services shouldn't be an antitrust issue either. After all, the MyGP app already houses 3rd party services.

Having the vision and driving the execution may be a challenge. The bureaucracy is particularly virulent in large companies such as GP, with employees buried under 8 or more layers of management.

Their interface and experience is not optimized for these use cases yet, but it's not a daunting task for the team there.

In fact, last week Pathao launched Pathao Health, in collaboration with some leading health-tech startups. They aim to serve 1 million users in the next 90 days.

Telemedicine can level regional differences since the same information can be accessed sitting at home as from a medical facility several thousand kilometers away.

In terms of cost, studies revealed that telemedicine service reduces the health care cost of patients to a great extent. Users had to spend even less than 1/10th the amount to access the same service in a conventional means of the service. This is possible through higher efficiency (doctors being able to serve more patients) and lower infrastructure costs.

It’s unlikely that telemedicine can replace physical clinics. Instead, the aim should be to harness technology and empower doctors to fulfill their calling of helping patients, bringing down the geographic and cost barriers many folds.

Security considerations are a major obstacle to telemedicine uptake. These include an absence of a legal framework to allow health professionals to deliver services in different parts of a country; a lack of policies that govern patient privacy and confidentiality vis-à-vis data transfer, storage, and sharing between health professionals and corporations; medical liability for the health professionals offering telemedicine services, health professional authentication and so on.

Disclosure: I work at Pathao, which gives me a good insight into the race for use cases among aggregators/platforms. I’ve tried my best to remain objective throughout this analysis.