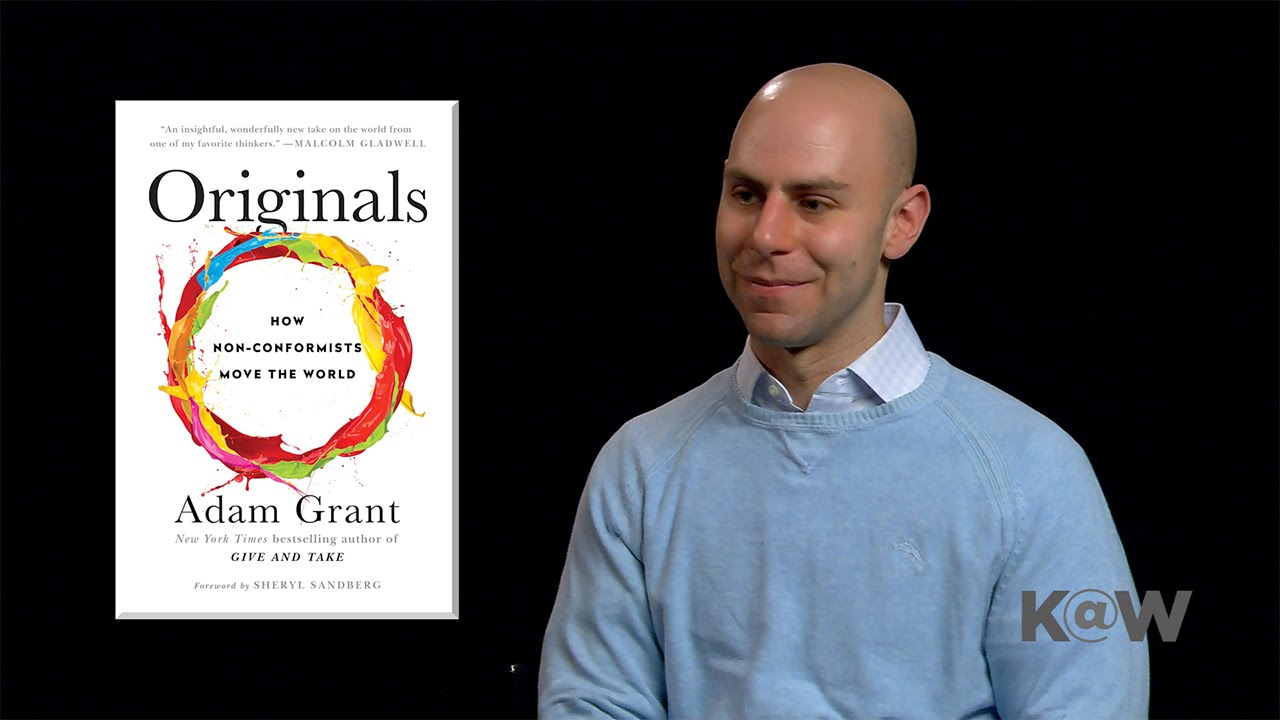

A new book by Wharton management professor Adam Grant challenges our assumptions about what it takes to generate and champion original ideas in ourselves and others. In Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World, Grant reveals what we can learn from entrepreneurs and other trailblazers to help us think differently and to make our voices heard.

Knowledge@Wharton recently sat down to speak with Grant about why he wrote his new book.

An edited transcript of the conversation appears below.

Knowledge@Wharton: You often interview authors in the Authors@Wharton series for Knowledge@Wharton, so I’m going to start with a question that you usually ask them: What inspired you to write this book?…

Grant: The inspiration for writing this book was twofold. One, I worked as a manager for a while before I came into academia. The one time I worked up the courage to speak up, I was actually dragged by my boss’s boss into the bathroom. I ended up being threatened that I would be fired if I ever spoke my mind again. I really wanted to know, how could I have done that more effectively?

Then more recently, since my first book, Give and Take, came out, people have been constantly asking, “If I am in a culture where people are constantly selfish, or toxic, how do I change that? If I’m facing undesirable circumstances anywhere, what do I do about them?” I didn’t feel like I had good answers for them. So I started doing a lot of research, and here we are.

Knowledge@Wharton: Great. So, you talk about entrepreneurship right at the beginning of the book, especially the company Warby Parker, which came out of the efforts of some Wharton students. Typically, when people think about entrepreneurs, they see them as the ultimate risk-takers, who are willing to bet the farm on their dreams. What is your view of entrepreneurship and the relationship between entrepreneurship and risk-taking?

Grant: That’s what I thought, too, initially. When I thought of an entrepreneur, I thought of a swashbuckling pirate or a daredevil, the kind of person who would basically leap before he or she looked. The data tell a completely different story: Entrepreneurs are not necessarily more risk-taking than the rest of us. In fact, they may even be more risk-averse.

“When I thought of an entrepreneur, I thought of a swashbuckling pirate or a daredevil, the kind of person who would basically leap before he or she looked. The data tell a completely different story…What a lot of them are doing is … managing risk portfolios.”

Most entrepreneurs hate gambling. What they really enjoy is the opportunity to try something new. They’re typically driven not by this craving for risk, but rather, this desire to say, “Can I pursue a passion? Can I work independently? Can I do something where I’m really going to have an impact?”

What mystifies a lot of us is we look at entrepreneurs, and we see them taking risks, and we assume they’re risk-takers. What a lot of them are doing is … managing risk portfolios. Think about it like a stock portfolio, right? If you’re going to make a risky investment in one realm, you’re supposed to offset that with a safer bet in a different stock. Entrepreneurs actually do the same thing with risk. At least the successful ones do. When they have to go out on a limb in one domain, they will actually be more cautious in another to cover their bases.

Knowledge@Wharton: You also have so many interesting stories in the book. One that I especially liked was about the internet browsers that people use. Does that say anything about the people who use them, and about their originality?

Grant: It says more than I initially expected. This economist, Michael Housman, was tracking data on customer service reps and call center employees. He found that employees who use Chrome or Firefox actually outperformed Internet Explorer and Safari users. They also stayed in their jobs significantly longer.

So I started stalking him, of course, to find out why. What’s going on? What does Chrome and Firefox do for you? It turned out it wasn’t a technical advantage. It was not that they were faster at typing. They didn’t have more computer knowledge. It was about how you got the browser. If you’re going to use Internet Explorer or Safari, it comes preinstalled on your computer. Right? Whereas Chrome and Firefox, if you want them, you have to take a little bit of initiative, and download a different browser.

That’s a signal, a window around what you do at work. The kinds of people who had that instinct, to say, “You know what? I wonder if there’s a better browser out there,” they were also the kinds of people who looked for ways to improve their own jobs. Ultimately, they were able to create a job where they were more effective and more satisfied.

Now, people hear about these data, and sometimes they say, “Well, wait. If I want to get better at my job, all I have to do is upgrade to Chrome or Firefox?” It’s about the kind of thinking that underlies that choice. Not just accepting the default that’s handed to you, but asking, “Is there a different or better option available?”

“We could all rely more on peer feedback and do a better job saying, ‘When I’ve got a new idea, I’m not necessarily going to trust my own judgment…. I’m going to go to people who are fellow creators.’”

Knowledge@Wharton: In thinking about originality, you said the biggest barrier to your originality is not the ability to generate ideas, but to select them. How can people avoid making bad bets when it comes to idea selection?

Grant: We’re all actually pretty terrible at this when it comes to our own ideas. The evidence is overwhelming. It’s hard to find an entrepreneur who doesn’t think his or her idea is a winner….

It’s really other people’s feedback that turns out to be important. There’s this brilliant research by Justin Berg, one of our former doctoral students who’s now on the Stanford faculty. Justin got circus artists to try to gauge how likely their performances were to succeed with audiences. They were terrible. They overestimated the success of their own performances by a lot. So then he went to managers, and he showed a bunch of videos. So you get to see some jugglers, you get to see a few clowns. By the way, nobody likes clowns, it turns out. Universally hated. You may get to watch a few aerial acrobatics performances. Then the managers make judgments. The managers are not very accurate, either. You tend to be too positive on your own ideas. Managers tend to be more negative on other people’s ideas because they have a prototype about what a great circus performance looks like. They are evaluating all the ideas that come onto the table in terms of, “Does that fit or not?” The group that was much more effective than either people themselves or managers was peers: fellow circus artists. So you might not be able to judge your own ideas, but you’re great at forecasting the success of other people’s ideas.

Because unlike managers, as a performer, you’re much more willing to look at an unusual act and say, “You know what? I’ve never seen anything like that before. But that has potential.” But you also are willing to say, “You know what? This is really bad.”

We could all rely more on peer feedback and do a better job saying, “When I’ve got a new idea, I’m not necessarily going to trust my own judgment. But I’m not always going to trust … middle managers who tend to be the most risk-averse and most conservative. I’m going to go to people who are fellow creators.”

Knowledge@Wharton: You have a couple of great examples from the business world of Segway and Seinfeld, in demonstrating this. Can you tell us a little bit about those examples?

Grant: Yeah. I think the Segway example is a case, unfortunately, of an entrepreneur being overconfident in an idea. So the short version of the story is, you have this idea for a self-balancing vehicle. You don’t really go out and figure out, is this something people would want to drive? Would they trust it? Would they buy it?

Whereas in Seinfeld, you have the exact opposite. Instead of a false-positive, it’s a false-negative. The pilot was rated weak, and it was actually initially scrapped. Then this TV executive, Rick Ludwin, who doesn’t even work in comedy – he was from the variety and specials department –sees the pilot, and he says, “This is really good.” He ends up finding a slot for it, using his own budget.

[Rick] was able to step outside of the prototypes that a lot of us tend to use. People look to the Seinfeld pilot, and they said, “It’s a show about nothing. This does not fit the mold of how a comedy or a sitcom is supposed to run.” Rick had come out of variety and specials, lots of different formats. He said, “You know what? Not every plot has to be resolved. Not every twist needs to go somewhere. The point is to make people laugh.” He was much more open to the potential there.

Knowledge@Wharton: Does that mean that when it comes to idea generation, quantity is very closely related to quality?

Grant: One of the myths that people carry around is if you want to be original, you will think, “I should do less because I want to perfect my invention or my creation.” But again, the data actually support the opposite story. Dean Simonton is a psychologist who has been studying this his whole career. What he finds is, one of the best predictors of how much creative productivity you will ultimately achieve, how much you’re regarded as a genius, is about the number of ideas you produce. The more ideas you create, the more variety you have. Some of those ideas are going to be blind alleys or random walks in bad directions. But you have a better shot then of stumbling upon something that’s really powerful.

For example, when you compare great composers, if you look at Beethoven, Bach, Mozart, it wasn’t that their average is so much better than their peers. It’s that they generated sometimes 600 or 1,000 different compositions. A few of those are considered true masterpieces. You can see this not just when comparing different kinds of people, though. You can also pick it up when you look within a person’s career. Creators are the most novel, the most original, during the times when they have the most bad ideas.

Look at Edison, for example. Great example. Edison made a talking doll so creepy that it scared not only children but adults, too. He came up with a fruit preservation technique that failed. He tried to mine in a number of ways that didn’t work out. It was during that window where he had over 100 failed ideas, that he was able to perfect the lightbulb. The idea is that you have to generate a lot of garbage to reach greatness.

Knowledge@Wharton: Now, one of the challenges that anyone who comes up with a new idea is going to face, is how do you get them heard? How do you speak truth to power? Can you give us some examples of how you can do that while minimizing the risk of damaging your career, as you felt at the start of our conversation?

Grant: I could have really used this advice a while back. One of the most important things that I’ve learned about speaking truth to power is that when we’re excited about an idea we tend to make the mistake of assembling as many reasons as possible to support it. By the time we pitch it, it seems as if we’re completely biased and blinded. It’s all, “This is a good idea.” There’s no balance whatsoever in the pitch.

There’s an entrepreneur, Rufus Griscom, who has a great antidote to this. He starts a company called Babble. It’s a parenting web site. He goes to investors, and he says, “These are the three reasons you should not back my company.” That year, he walks away with over $3 million US in funding. Two years later he goes to Disney and says, “I’m interested in selling this company to you. Here are the five reasons why you should not buy it.” They end up buying it for $40 million.

“I thought you had to be an early bird, a first mover. But again, the evidence proved me wrong. Turns out that most originals are great procrastinators.”

Now, of course, part of this is it’s a little bit of an attention-grabbing device, right? You don’t expect an entrepreneur to say, “Here’s why you should not trust me.” But what’s interesting is, when Rufus acknowledges the weaknesses of his idea, he looks like he’s self-critical and honest. He also makes it harder for people to come up with their own objections. Because as they’re thinking about their own concerns, they say, “You know what? He hit three of my four. This guy must be so confident that he can overcome these issues that he’s willing to admit those weaknesses out loud. Those strengths must be powerful enough to offset them.”

We can all do a better job probably giving a more balanced case for our ideas when we speak truth to power. The other thing that I would recommend is to avoid a mistake that I made, which is, when I went to speak up in my own career, I looked for the friendliest, most agreeable person, assuming that’s the person who’s ultimately going to be supportive. But it turned out that that person didn’t have my back. Because just as he was interested in being nice to me, he also wanted to keep the peace with everyone else.

What I should have done, and what the evidence supports, is that if you go to a more disagreeable boss — somebody who tends to be a little bit more critical, skeptical and challenging — that person’s going to be tougher on you. But then they will be also more willing to rock the boat a little bit and stand up for your idea if it’s unpopular.

Knowledge@Wharton: Interesting. When is it the right time to exit an organization, rather than continuing to make the case for an idea?

Grant: This is a problem that a lot of us struggle with. I don’t know that I have any answers to it. I do know, though, that if you track what happens to most people who speak up, usually they try voicing their idea. Then if it doesn’t work out, they either decide, “You know what? I don’t have other options, and I need to keep this job.” Or they start to look elsewhere.

There are a couple of tests, though, that are worth running, before you decide to leave. The first one is, have I gone to all of the potential allies that I have in the organization? The second one is, is it possible that there’s a better way for me to present this idea, that it’s not that people are unwilling to hear it? It’s just that they didn’t see the potential, because I didn’t speak about it effectively.

Third and most importantly, the question is, what am I ultimately trying to accomplish? Is this organization the best site for me to reach my goals? If you can answer those three questions, “I can’t succeed on any of them,” it’s probably time to start looking around a little bit.

“We all need allies. It’s very hard to be a lone original.”

Knowledge@Wharton: Sometimes people procrastinate about some of these things. You have some interesting ideas about procrastination in your book. Do you see procrastination as a strength or as a weakness?

Grant: My stance on this has completely changed, partially during the process of writing the book. If you want to be an original – the kind of nonconformist who champions new ideas and really drives creativity and change in the world – I thought you had to be an early bird, a first mover. But again, the evidence proved me wrong. Turns out that most originals are great procrastinators. Twitter They’re constantly putting things off. I actually had a former student, Jihae Shin, who showed that if you procrastinate a little bit, you will generate more creative ideas than if you dive right into a task or finish it right away.

The reason for this is pretty simple. I’ve actually been a victim of the opposite of it for a while. I am actually a precrastinator. I’m somebody who, if I know I have something due in six months, I will feel urgent pressure to do it now and worry about it constantly, until the moment that it’s done. What I noticed as I compared that against the originals that I studied, the people that I interviewed, the data that I gathered, was a lot of them were waiting for the right time. If they put off the start or completion of the task a little bit, they allowed themselves to access more diverse ideas. They saw possibilities that I wouldn’t have seen.

Because our first ideas are our most conventional, typically. You have to sort of weed out the familiar in order to get to the much more unusual and original. I wasn’t doing that when I dove right into a task. So I’ve come to believe we should all procrastinate deliberately. But if you push that too far, of course, you’re just not going to have time to finish your work.

Knowledge@Wharton: What is strategic procrastination?

Grant: I think of strategic procrastination as essentially this idea of waiting for the right time. So as a writer, for example, I have learned to leave drafts unfinished, on purpose. What I will do is, I’ll start working on a draft. I really want to spend the next two hours finishing it. I will put it away. Three days later, when I come back, I have seven or eight new ideas that I would never have considered, because now it’s in the back of my mind. We have a much better memory for incomplete than complete tasks. The moment I hit send on that draft, it’s out of my mind, whereas when I leave it open, then I’m constantly processing it. I’m seeing new possibilities.

The other thing I’ve learned to do over time is I’ll finish a draft, but I won’t actually submit it or ship it. I’ll leave it sitting for two or three weeks. By the time I come back to it, I have enough distance to say, “Who wrote this drivel?” But I also, then again, am able to approach it with a fresh perspective. For me, that’s what strategic procrastination is all about.

Knowledge@Wharton: Especially in writing. When you say something in the heat of the moment, in the heat of writing, you don’t have enough distance to be objective about it.

Grant: Exactly.

Knowledge@Wharton: I got very similar advice from one of my early editors in my career. I always appreciated that.

Grant: I think it’s wonderful advice, as long as we find that sweet spot, right? Of procrastinating enough to allow the ideas to incubate, but not so much that you run out of time and you just have to pick the simplest idea.

“You need to get people … feeling comfortable being uncomfortable.”

Knowledge@Wharton: Exactly. Now, Einstein believed that people are most creative when they are young. Is that true?

Grant: It seemed to be true for Einstein but not for most of the rest of us. So, the story of Einstein is actually pretty sad if you look at it. So, transforms physics not once but twice, with special and general relativity. Then he ends up opposing the next major revolution in physics, which is quantum mechanics. Ironically, his opposition to it is debunked, because he forgot to account for his own theory of relativity. Whoops. So Einstein said, reflecting on this experience, that to punish him for testing and challenging authority, the fates made him an authority himself. That suggests that at some point we are all doomed, once we’ve internalized ideas, to essentially lose our creativity.

When you study, though, great scientists, musicians, poets, artists, what you see is that there are basically two cycles. One is basically the young genius. This is the Einstein, somebody who comes into a field, accumulates knowledge really quickly, but also has enough distance to not drink the Kool-Aid. That person ends up with a flash of insight coming up with a wildly different way of looking at the world. If that’s your style, you’re at risk for becoming too entrenched, and starting to take for granted so many assumptions that you can’t really think differently in that field anymore.

But there’s a second path, which was the Old Master. These are the people who tended to work much more experimentally. They were doing lots of little trials and errors. They were doing tasks, they were iterating. They were learning from the data, as opposed to having these eureka moments. They actually tended to peak frequently in their 40s, 50s, 60s, even 70s and 80s in some cases. There is hope for those of us who are more tortoise than hare.

Knowledge@Wharton: How can originality be sustained over time?

Grant: One of the challenges that we all face if we want to sustain originality is we have to keep our exposure to fresh ideas. The longer you spend in a field, an organization, a job, the more familiar certain things will become. You have to push yourself outside of that comfort zone.

How do you do that? There’s a study I really enjoy by Frédérick Godart and his colleagues, where they actually track fashion designers. They look at what predicts which fashion houses have the most creative and original designs. It turns out, one of the best predictors of that is [whether] the creative director of that fashion house lived abroad. Then, if you break down the data, it goes further. Living abroad alone is not enough. You have to work abroad. You actually have to use the ideas of the culture, not just sort of visit and enjoy it as a tourist. You have to internalize how that culture thinks and looks at things differently.

Then working abroad, you can break that down further and say it’s more beneficial for your creativity and originality if you work abroad in countries that are more different from your own and if you stay there longer. So that kind of breadth is what we’re looking for.

How do you simulate that? I think what a lot of us can do is, we can do a much better job with the job rotation, for example. In your own organization, spend two days doing a job that you’ve never done before. It gives you a completely fresh perspective on the work. Go do a site visit to a different organization. Or even a company that’s in a different field from your own, different industry. And all of a sudden, you have lots of ideas that you can apply to your own work.

Knowledge@Wharton: What role do coalitions play in bringing original ideas to life?

Grant: We all need allies. It’s very hard to be a lone original. I think Derek Sivers put it well: “[The first] follower is what transforms a lone nut into a leader.” Nobody wants to be that lone nut. Many of us, though, assume that we need large coalitions to support our ideas. But most of the time, research by our own Sigal Barsade shows that even a single ally, a single friend, is enough to make you feel that you’re not lonely. Coalitions typically are much more about finding that very, very small group of people who believe in you and are willing to give your ideas a shot. As opposed to saying, “I need to get 74 percent of this organization on board.”

Knowledge@Wharton: You also talk about something called a Trojan horse strategy for coalition-building. What’s that?

Grant: Well, this was introduced to me by Meredith Perry, who’s a brilliant entrepreneur. She’s the founder of UBeam, which is trying to bring wireless power to the world. When Meredith started her company, she had this idea that you could actually transmit electricity through the air and power up different kinds of devices – phones, computers – without any kind of cord. People didn’t believe her. She tried to hire the very best engineers, because she couldn’t build the product on her own. They said, “That’s impossible. It defies the laws of physics.”

She was convinced that they were wrong. In order to get them to come on board, she changed her pitch to them. Instead of saying, “I’m trying to build wireless power. Can you make me this kind of transducer?” She just said, “I’m trying to build a transducer. Can you make me this part?” She actually disguised her purpose because it was too radical for most people to understand.

Then a bunch of engineers came on board, and she was able to work with them to make it happen. What she did was, she smuggled her real vision, in that case, inside a Trojan horse. She’s really trying to build wireless power. But she has a bunch of people working on different pieces that ultimately will come together for a different outcome than they intend.

The more radical, the more original your idea is, the more important it is to make sure that people aren’t dissuaded by the end, and instead focus them on perhaps a more moderate goal that they think is plausible.

Knowledge@Wharton: Does originality have roots in family? For example, does birth order matter in originality?

“Cohesive groups often make the best decisions. People frequently when they trust each other are willing to challenge each other and say, ‘I know this person is not going to take this too personally.’”

Grant: It matters more than I expected going in. There’s a huge debate about birth order. I would say the jury is still out, overall. But there is compelling evidence that firstborns, on average, tend to be a little bit smarter and a little bit more likely to achieve conventional success in fields like politics and science. We have more elected officials who are firstborn, for example. We also have more Nobel prize-wining scientists.

However, when it comes to originality, completely changing the way that a field operates or introducing a new technology, there does appear to be a later-born advantage. There are a couple of reasons for that. One is that later-borns are given more freedom. So by the time you have three or four older siblings, you’re allowed to do a lot of things that they weren’t allowed to do growing up. You get to take some risks.

The other thing that happens is, some of the more conventional achievement niches are filled. You may have an older sibling who’s the academic star, and one who’s an athlete. You need to find other ways to differentiate yourself. One of those can be creativity. I was interested in tracking this, as you know, with comedians. So I took Comedy Central’s list of the 100 greatest stand-up comics of all time, which had some great originals. People like Chris Rock, George Carlin, Jerry Seinfeld. I studied their birth order and found that they were more than twice as likely to be born last in their families as first. The odds of that happening by chance alone are two in a million. So I think there is perhaps an advantage for later-borns in originality. As a first-born, I was not excited by this research.

But the good news is that birth order effects are not set in stone, so giving children the kinds of freedom, encouraging them to find unique niches to express themselves, can push all of us, even us firstborns, in a more original direction.

Knowledge@Wharton: I wonder if you could talk about that in a little more detail. How can parents nurture more originality among their children?

Grant: Role models play an important part of this process. So, what a lot of children do is they become unoriginal because they’ve only been exposed to models or standards who are very familiar and conventional. So children grow up. They see lots of engineers, doctors, lawyers, teachers, and they say, “That’s what I want to do, too.” As parents, we can open up more original niches by exposing children to a much wider variety of occupations, careers, ideas. Some of the most original possibilities are not going to exist yet.

Which is why when you listen to what some of the great originals in the technology world say, they will frequently identify their inspiration in science fiction. Books like Ender’s Game. Now we’re probably going to see more Harry Potter references when we ask the next generation of entrepreneurs , “What inspired you?” But it’s amazing how many inventions come out of fictional stories. We could do a much better job making sure that children are exposed to lots of ideas that don’t exist yet, so that when they see, for example, the next generation of somebody using what looks a lot like a mobile phone in a 1960s Star Trek episode, they say, “You know what? I want to go out and create that.”

Knowledge@Wharton: When you consider families, or even companies, one of the biggest problems seems to be groupthink. How does that come about, and how can you prevent it?

Grant: A lot of people attribute groupthink to cohesion. They think that if we’re too close, if we trust each other too much … then we’re not going to challenge each other. That turns out to be false. Cohesive groups often make the best decisions. People frequently when they trust each other are willing to challenge each other and say, “I know this person is not going to take this too personally.”

But if you’re not careful, cohesion can take you down a path toward groupthink, when people become more concerned about politics and about maintaining their relationships and reputations than about speaking their minds and being honest. So most leaders try to combat this by assigning devil’s advocates. I know that there’s a majority preference in the room, so I’m going to assign one person to be the opposite.

Devil’s advocates, according to the research, don’t work very well most of the time. Charlan Nemeth at Berkeley has been studying this for over four decades. What she shows is, devil’s advocates make two mistakes. One is, they tend to give lip service to an idea but they don’t really believe in it, so they don’t sell it. Secondly, when devil’s advocates speak, people know they are just playing a role. I don’t need to take you seriously. “Okay, I’ve pretended to advocate for this position, and now we can go back to the majority preference.”

Instead of assigning a devil’s advocate, what we all need to do is unearth a devil’s advocate: genuine dissenters, people who actually hold the minority opinion. We need to find those people. We need to invite them into the conversation, and give them a voice. What’s so powerful about that is, it turns out minority opinions are useful even when they’re wrong. Let’s say we’re going to hire one of four candidates. Almost everybody in the room prefers candidate A, and candidate B is really the best one. If someone comes in and advocates for candidate C, we will have a better shot at choosing, ultimately, the right candidate of B. Because when divergent information comes to the table, we’re much more likely to reevaluate our assumptions, consider new criteria, and make a better decision.

Knowledge@Wharton: To conclude this fascinating conversation, I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how organizations can create a culture of nurturing originality.

Grant: If you want a culture where originality thrives, as opposed to being stifled, there are a couple things to do. One is, you have to make it safe for people to fail. You have to make it okay for ideas to come up that don’t go anywhere. Because if you squash all the bad ideas, you’re going to miss out on some of your most original possibilities. A second step that turns out to be really critical if you care about originality in your organization, and especially if you want it to be a core part of the culture, is you have to think differently about hiring. A lot of leaders hire on culture fit. They say, “Look. I want people who share our values, who match the culture.” That’s actually a recipe for groupthink. You hire a bunch of people who look at problems in the same way, who have the same opinions, the same principles.

Ideo, the design firm, has a compelling alternative to this. They say, “Look. We’re going to throw cultural fit out the window. Instead, we look for cultural contribution. So when we hire, we’re not looking for people who are going to replicate or clone the culture. We’re going to find people who enrich the culture. The test of that is to figure out what’s missing from your culture, and then try to bring in people who can embody that.

The third thing to do if you want to build a culture of originality is, you need to challenge the status quo a lot. You need to get people – as Bob Sutton at Stanford would say – feeling comfortable being uncomfortable. One of my favorite ways of doing that is from Lisa Bodell at Future Think. She actually runs this “Kill the Company” exercise, where she brings leaders together and has them spend maybe an hour or two brainstorming ways to put their own company out of business.

I’ve seen this done in financial services and pharmaceutical companies. I’ve never seen executives so excited, as when they finally get to trash their own employer. But what’s interesting about it is it shifts their mindset. Instead of playing defense and protecting themselves against competitive threats, they’re on offense.

They get to try all these new possibilities and drill into them. Then after that, when they shift back to thinking, “How do I defend against these threats,” they have much more creativity at their disposal. I think that’s a good example of shaking things up a little bit.

Note: This article was originally appearred on Knowledge@Wharton blog, republished with permission