Generally speaking, global food brands follow a somewhat predictable pattern. American burgers scale from the United States. Italian pizza chains trace their lineage to Naples or Rome. Japanese ramen concepts expand from Tokyo. The brand story and the business headquarters align with the product's cultural origin, and both typically sit in developed markets with established consumer credibility.

There are examples where this pattern breaks, where the cultural origin of the food is maintained, but the scale is done by a third brand.

Nando's built a global chicken brand from South Africa by leveraging Portuguese-Mozambican peri-peri heritage; the product had cultural credibility even if the company didn't originate in a traditional power center. Jollibee grew from the Philippines by targeting diaspora communities first, then expanding to mainstream markets once it had proven unit economics and operational systems.

These exceptions tend to share common traits: they either carry authentic cultural credentials for their product category or they prove the model in underserved markets before attempting direct competition with established players.

Waffle Up is designed differently and tries to borrow from both the standard pattern and these exceptions. It's a Singapore-anchored food-tech QSR brand, with operations and R&D executed primarily from Bangladesh. It's a deliberately structured global brand that decouples legal domicile and brand positioning from operational execution. IP and customer perception anchor in Singapore. Product development, technology infrastructure, and talent concentration happen in Dhaka. The model inverts the traditional assumption that global consumer brands must be built where they're headquartered.

The company operates 16 waffle outlets across Bangladesh and Singapore and claims to have sold over a million waffles since launching in 2021. It ranks as one of the most popular brands on several food delivery platforms in Bangladesh and is working to do the same in Singapore. Individual outlets are reportedly highly profitable, though the organization remains in investment mode as it scales. The company employs over 100 people globally, with significant operations based in Dhaka, and plans expansion into Indonesia, Bangkok, and Dubai in the coming months.

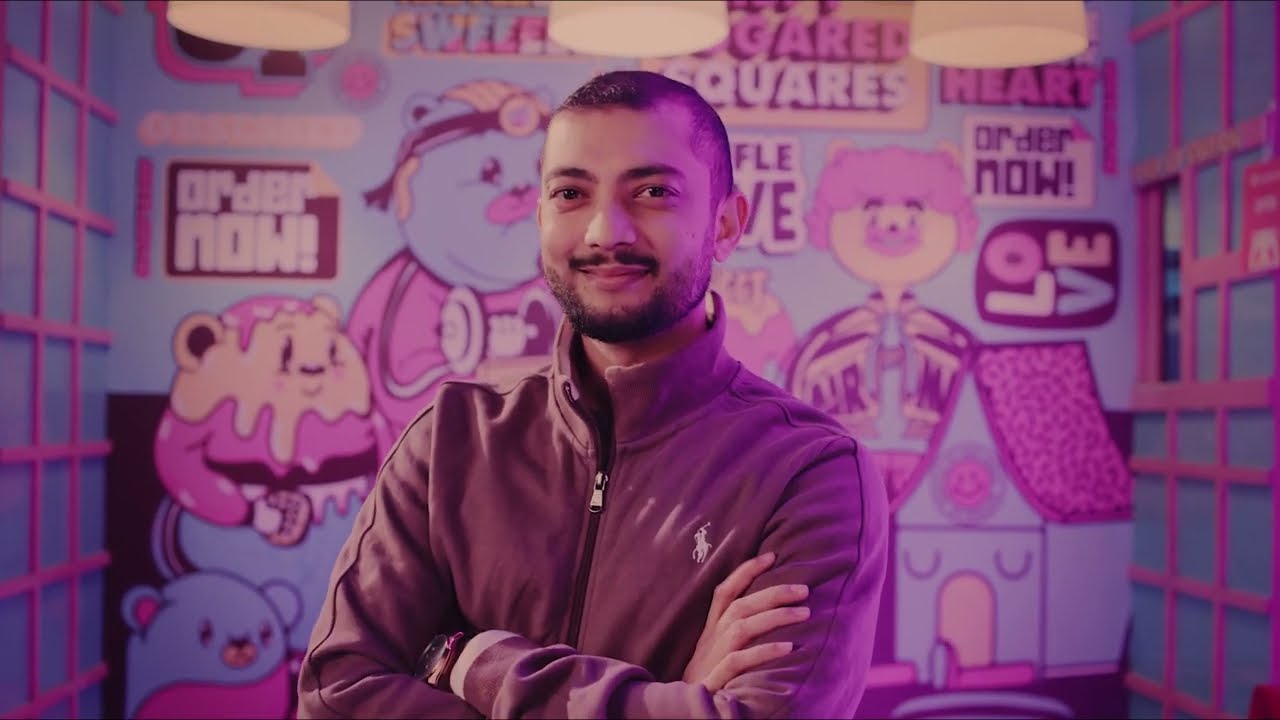

Founder Salman Goni, a passionate food and restaurant founder turned food-tech entrepreneur, wants to build what he calls a "virtual global brand", a waffle chain comparable to Krispy Kreme or Dunkin' Donuts in scale and recognition, but structured fundamentally differently from traditional restaurant franchises.

Where conventional chains invest in real estate and physical presence, Waffle Up invests in data infrastructure and operational systems. Where traditional franchises require significant local capital deployment, Waffle Up's warehouse-to-outlet model is designed for capital-light geographic expansion.

Salman's background makes him an unusual founder for this challenge. He spent nearly a decade building restaurant businesses in Bangladesh, starting with Treehouse in 2015 after leaving an MNC job. That experience taught him the operational realities of food service: supply chains, quality control, and the challenges of maintaining consistency across locations. He also built Yoda Technologies, an EdTech platform that won the National ICT Award before he shut it down during COVID-19 to focus on restaurants. What emerged is a restaurant operator who thinks like a tech entrepreneur, combined with a genuine obsession for food innovation.

"You have to understand the food," he emphasizes. "You can't just copy another restaurant." Salman is a food connoisseur who tastes obsessively. When he travels, he seeks out local specialties. In Dhaka, he has his favorite joints in every category. He goes to a specific street food stall near the airport because "there's a guy who makes fuchka [a popular Bengali snack] differently. Just because everyone sells fuchka doesn't mean they're all the same. He does something new. My loyalty to him still exists."

This combination, operational expertise from years running restaurants, systems thinking from building technology platforms, and genuine domain obsession with food, underlies everything Waffle Up attempts. The company isn't just a restaurant chain trying to use more technology. It's a food-tech company that happens to sell waffles, built by someone who understands both the food operations and the technical infrastructure required to scale globally.

This article examines the strategic thinking behind Waffle Up's approach: how the company identifies its market opportunity, what operational innovations enable the model, how the virtual brand structure actually works, and whether the combination of food expertise and technical infrastructure can support the company's global ambitions.

The strategic question isn't whether waffles can be a global category; desserts clearly represent a massive market. It’s neither about whether Waffle Up can open outlets in multiple countries, plenty of restaurant chains manage that. The test is whether this specific architecture, Singapore brand anchor plus Bangladesh execution base plus food-tech infrastructure, can create a genuinely global consumer brand while maintaining the quality and brand consistency and structural advantages that make the model work.

Waffle Up's thesis starts with a specific observation: while major categories have dominant global players, Krispy Kreme and Dunkin' for donuts, Domino's and Pizza Hut for pizza, McDonald's and Burger King for burgers, waffles remain fragmented.

"Everyone has made donut brands, KFC, Dunkin' Donuts, Krispy Kreme. Or McDonald's for burgers, Domino's for pizza. But for the dessert segment, specifically waffles, no one has cracked it globally," Salman explains.

The waffle category is associated with Belgium but lacks a dominant branded player. Local waffle shops exist in most markets, and established chains occasionally offer waffles as menu items, but no brand has done for waffles what Domino's did for pizza or Krispy Kreme did for donuts: create a standardized, scalable, globally recognized product.

Salman points out that the global dessert market is worth billions of dollars. Capturing even a small percentage would create a substantial business. The question is execution.

Salman studied how existing global food chains achieved scale. His examination of pizza is instructive: "Pizza is technically a Mediterranean dish, derived from pita bread, but Italians successfully branded it as their own. Domino's then revolutionized the category by putting pizza in boxes and pioneering home delivery. They realized people don't always want to travel; they want to make a call and get pizza at home."

The insight: Domino's didn't succeed by making better pizza than Italian restaurants. They succeeded by making pizza more convenient through delivery infrastructure and standardization. Innovation was operational, not culinary alone.

Similarly, McDonald's didn't invent hamburgers, but they standardized production so the product became reliable and consistent across thousands of locations. KFC didn't invent fried chicken, but Colonel Sanders developed a recipe and process that could be replicated globally with minimal skill requirements.

The pattern: successful global food brands combine three elements. First, a unique and high-quality product that can be standardized and systematized. Second, operational innovation that makes the product more accessible (delivery, drive-through, app ordering). Third, geographic scalability through a model that works in multiple markets without massive local infrastructure investment.

For waffles, Salman saw operational barriers preventing this combination. Waffles were perceived as a sit-down dessert served in Belgian-style waffle houses. The product didn't travel well, the desserts melt. Most waffle preparation required skill and judgment from operators.

Waffle Up's strategy addresses each barrier. The company engineered waffles specifically for delivery, using packaging and recipes designed to maintain quality during transport. The company developed standardized recipes executable by using specialized equipment. "If you go to McDonald's or KFC, you won't see a 'chef.' You see a normal service crew running it. Everything is automated."

The goal was to create a waffle product that worked within the Domino's model, standardized, delivery-friendly, and executable by trained staff rather than skilled chefs. "I realized you need people you can trust and a recipe you can protect," Salman says.

This required genuine domain expertise. Salman describes his process: "I couldn't learn how to mix batter myself, I mean, I could, but is it worth it? You don't do everything yourself; you delegate." But delegation came only after Salman understood the fundamentals well enough to create systematic processes. His years running Treehouse gave him that foundation.

The company now uses what Salman describes as "machines, recipes, and SOPs" controlled entirely by the company. The system is designed so that product quality depends on the following procedures rather than individual judgment, the same insight that allowed McDonald's to scale globally with teenage employees.

Salman positions Waffle Up explicitly as a food-tech company rather than a restaurant chain. His reference points span multiple Asian food-tech models: Chagee's brand-driven supply chain mastery, Flash Coffee's digitally native Southeast Asian expansion, and Luckin Coffee's automation-first approach.

"FoodTech is relatively new. Most countries don't even acknowledge 'FoodTech'—they just think of it as food delivery. But FoodTech can be a virtual food brand from the global market."

The distinction matters for how the company structures and scales. Traditional restaurant chains invest heavily in real estate, interior design, and front-of-house operations. Each outlet is a significant capital investment. Food-tech companies, in Salman's conception, invest primarily in technology infrastructure, data systems, and supply chain coordination. Physical outlets serve both as fulfillment points in a network and standalone businesses.

"We are an omnichannel brand where the backend deals with logistics, and the front end deals with customers."

The food-tech model inverts traditional restaurant economics. Instead of building valuable real estate assets and brand locations, the company builds valuable data assets and operational systems. Instead of each outlet being a separate P&L, outlets become nodes in an integrated network.

Chagee demonstrated how brand identity and supply chain control could drive rapid expansion across Asia. Flash Coffee showed that mobile-first ordering could create viable businesses without traditional storefronts. Luckin Coffee proved that heavy automation could enable massive scale with minimal per-location overhead. "Just like you can order coffee via an app in some countries without human interaction, we want to leverage that," Salman notes.

Waffle Up borrows selectively from each model rather than copying any single playbook. Like Chagee, it emphasizes brand distinctiveness and supply chain control. Like Flash Coffee, it's built for app-based ordering from inception. Like Luckin, it uses standardization and data to reduce operational complexity.

This thinking shaped Waffle Up's structure from inception. Every outlet uses the same POS system, follows identical SOPs, sources from the same warehouse network, and feeds data back to central analytics. "We control every aspect: POS, machines, recipes, and SOPs. The company owns everything."

The goal is to make outlets interchangeable and scalable, more like franchise units of a tech platform than artisanal food businesses. Quality and consistency come from systems, not individual location management.

From day one, Waffle Up collected customer names and phone numbers with every order. This practice, standard in developed markets but less common in Bangladesh's restaurant scene, creates a proprietary customer database enabling everything from inventory optimization to direct marketing.

"Most restaurants don't understand data. The sales data they have is 'dead data.' They know they sold an item, but they don't know which customer came back. You don't have customer data."

The distinction is significant. Dead data tells you what happened. Customer data enables prediction. If you know Customer X orders every Friday evening and typically spends 800 taka, you can optimize inventory for Friday evenings, send targeted promotions on Thursday, and calculate customer lifetime value.

"If you take the name and number of every customer from day one, you can predict things," Salman explains. The data enables demand forecasting, optimizes which products to promote, identifies high-value customers for retention, and measures marketing campaign effectiveness.

Implementing this in Bangladesh required technical sophistication. Third-party delivery platforms provide what Salman calls "ambiguous reports" without proper APIs. "In Singapore, we get the API from Foodpanda directly to our POS solution. In Bangladesh, we had to scrape the data using AI agents to connect the dots."

Waffle Up built AI agents that scrape data from multiple platforms and compile it into unified reports. This infrastructure, largely invisible to customers, gives the company a clearer picture of demand patterns, customer behavior, and operational efficiency than competitors relying on platform-provided reports.

The company also developed "Surprise Cards", physical collectible cards with unique serial numbers that might contain free merchandise or loyalty points. Customers register cards on Waffle Up's platform to claim rewards. "We are trying to build an ecosystem of loyalty, rather than just sending 'nonsense' SMS to customers." The cards create a secondary data collection mechanism while building direct customer relationships outside delivery platforms.

This data infrastructure is central to Waffle Up's food-tech thesis.

Traditional restaurants treat each transaction discreetly. Food-tech companies treat each transaction as a data point in an ongoing customer relationship. The cumulative data becomes a competitive advantage that compounds over time, enabling better inventory management, more effective marketing, and a deeper understanding of customer preferences.

Most food chains scale through a hub-and-spoke model. A central kitchen prepares food, then distributes it to outlets. Waffle Up deliberately takes a different approach.

"This is the secret sauce: We do NOT have a Central Kitchen. Most people start with a hub-and-spoke model. We are shifting to a Warehouse-to-Outlet model."

In Waffle Up's system, third-party manufacturers produce ingredients to company's specifications. These ingredients go to a warehouse functioning as a distribution center. Individual outlets receive ingredients and handle final production following standardized SOPs.

"Manufacturers send ingredients to our warehouse. From the warehouse, it goes to the outlets. The outlets do the final production. This makes it a very lean model."

The claimed advantages: lower capital requirements (no central kitchen investment), easier geographic scaling (no radius limitations from a central hub), and reduced operational complexity. "If you have a central kitchen, your scalability is limited." A central kitchen can only service outlets within delivery range. The warehouse model allows outlets in different cities or countries without building kitchen infrastructure in each location.

The company controls recipes, SOPs, equipment specifications, and POS systems, but outsources actual production. This aligns with Salman's food-tech vision. Rather than owning heavy infrastructure, the company owns intellectual property (recipes, processes, brand) and technology infrastructure (data systems, ordering platforms, customer relationships). Physical production is outsourced to specialists, similar to how Apple outsources iPhone manufacturing while retaining design control and customer relationships.

The model carries risks. Quality control becomes harder when production happens at third-party facilities. Recipe iteration requires coordinating with external manufacturers. The company becomes dependent on supplier relationships in each market.

But Salman's years running Treehouse taught him the operational burden of running a central kitchen, equipment maintenance, inventory management, and labor coordination. By removing the central kitchen, Waffle Up eliminates one of the most operationally intensive components of traditional restaurant scaling.

Waffle Up is legally headquartered in Singapore. Operations and R&D happen primarily in Bangladesh. This structure reflects intentional architectural design.

"I wanted to open in Singapore. So I realized, I should open a brand in Singapore that will be a 'Virtual Waffle Brand' from Singapore. Then I started doing my R&D in the backend."

The logic: IP and brand credibility anchor in Singapore, a market with established credibility across Southeast Asia. Execution, talent development, and product iteration happen in Bangladesh, where the company can move faster and build more systematically. Bangladesh offers lower operating costs for R&D and talent. It's about building a structure optimized for global scalability from day one.

The company, registered in Singapore in 2020, secured trademarks for global and local operations by 2021, and opened its first outlet with minimal capital and a single employee. The company spent nearly two years on product development and four months on branding before launching in Dhaka. This was a deliberate investment in getting the fundamentals right before entering any market. Bangladesh outlets technically operate as franchises of the Singapore entity, though all remain company-owned. This creates a legal and brand structure designed for international expansion.

The "virtual" aspect extends beyond legal structure. Salman envisions Waffle Up operating in markets without maintaining a significant physical presence in its brand home. "You don't need a physical presence everywhere to be a global brand." A customer in Jakarta could order Singaporean waffles through an app, with products delivered from a local cloud kitchen, without Waffle Up maintaining substantial Singapore infrastructure.

This model only works if technology infrastructure can coordinate operations across markets, which is why Salman emphasizes that Waffle Up is "food-tech" rather than just "food."

Waffle Up employs over 100 people globally, with significant operations based in Dhaka. This includes technical staff, designers, and operational personnel. "We realized the market has amazing talent that usually gets exported to places like Google or Amazon. People usually talk about Bangladesh's cheap labor, but no one talks about the potential of white-collar people who could work for Google or Amazon. We are building a global brand using these resources."

The arbitrage is straightforward: hire skilled workers in Bangladesh at salaries competitive locally but lower than in Singapore or Western markets. Use this talent to build global brand infrastructure, design, technology, and marketing that would be prohibitively expensive elsewhere.

Salman frames this as a structural advantage for emerging market founders. "I am a founder from Bangladesh. I started with five guys. But we don't need to earn dollars to spend dollars. You can spend money in Taka, learn and fail in Taka, while building for a dollar market."

The strategy: use Bangladesh's lower costs to build and test the model, then export to higher-value markets where the brand captures Singapore-level pricing while maintaining Bangladesh-level cost structures.

For a food-tech company, much value creation happens in technology development, data analytics, and brand design, all doable remotely from low-cost markets. Physical operations require local presence, but the systems coordinating those operations can be built anywhere.

The brand aesthetic is deliberately distinctive. Pink balloons, cartoon characters based on Singapore's Merlion (rebranded as "Marlulu"), and Instagram-friendly packaging. Salman describes making waffles "emotional" rather than just functional.

The company spent months designing its branding and messaging. Its retro teal, pink, and secondary yellow colors reflect the vibrant vibe. The colors are also incorporated in its packaging. It also sells teal-colored waffles, which comes from the idea that food is also an essential part of branding, so why should it not represent the brand color? It has also launched a merchandise line in partnership with Dhaka-based clothing brand Gorur Ghash. It also introduced several characters that represent its brand. From packaging to its waffle sticks, every element it uses is designed in a manner that tells a particular story.

"Waffles shouldn't be just for the sake of filling your stomach; it should have emotion attached to it." The company won several Best Brand Awards within a short time, though Salman remains pragmatic: "Awards just boost ego; real business is about validating yourself through profitability and scalability."

The brand positioning is explicitly Singaporean despite Bangladesh-based operations. Salman frames Waffle Up as a "virtual global brand" that doesn't need physical presence in its brand home to be authentic.

Operationally, the company adapts to local markets while maintaining global positioning. In Bangladesh, some outlets stay open till 3:00 am and are available on online platforms 24 hours in the Gulshan and Banani area, unusual for the category. And its outlet in Singapore usually serves customers till 3:00 am. "No one stays open at this time in Singapore usually, especially waffle shops." This reflects Salman's direct understanding of customer behavior from years running Treehouse, knowing when customers want dessert, when foot traffic peaks, and when competition is lowest.

Extended hours also align with the food-tech model. App-based ordering makes late-night service more economically viable because customers order for delivery without requiring full front-of-house staffing. The outlet becomes primarily a production facility rather than a dine-in restaurant.

Waffle Up has been copied in Dubai, the Middle East, and Bangladesh, Salman says. His response reveals his competitive philosophy.

"My copycat will always get offended when his copycat copies him. I won't, because I was built with the mindset that copying is normal; it validates you. If you become arrogant and think, 'Let everyone copy, I don't need to improve,' you will lose. But if you keep improving, copying just proves you are leading."

The company keeps recipes secret and controls production through proprietary equipment and SOPs, but Salman doesn't believe these create an insurmountable moat. His bet is on operational excellence, brand strength, and data-driven optimization. Moat is what you do every day.

For a food-tech company, defensibility comes from the integrated system, data infrastructure, customer relationships, and supply chain coordination, rather than any single component. A copycat can replicate pink branding and similar recipes, but can't easily replicate four years of customer data, optimized inventory systems, and supplier relationships.

Salman claims individual outlets are "extremely profitable" but acknowledges overall organizational profitability remains a work in progress. "Our outlets are extremely profitable, but we are changing organizationally to become even more so."

This is common in scaling businesses: unit-level profitability exists, but corporate overhead and expansion costs keep overall operations in the red. The key question is whether unit economics are strong enough to eventually absorb central costs at scale.

Salman doesn't provide specific numbers but describes reaching organizational profitability while continuing expansion as the goal. "Unlike some startups that look for a quick exit, I am here to build an enduring business."

The financial structure has been funded through founder-injected capital and retained operating earnings, rather than institutional debt or venture subsidies. The expansion to date has come from operating cash flow and personal capital that Salman has reinvested into the business.

Salman is explicit about his capital approach: "If you are raising capital, you must be careful. Building a brand first makes more sense than scaling fast. Scaling is easy, but surviving for the long run is difficult."

This reflects a deliberate choice to prioritize brand-building and unit economics before seeking institutional capital. Waffle Up wants to be capital-selective. The company plans to raise institutional capital in the coming months, but on its own terms.

Salman says that when he plans to raise equity capital, he wants to do it with a strong foundation, when the fundamentals of the business are solid. The preference is for family offices, individuals, and VCs who value brand durability and unit economics over hypergrowth metrics.

The idea is to prove the model works profitably at the unit level, build brand equity organically, then use capital to accelerate what's already working rather than to discover what works.

The company currently operates 16 outlets across Bangladesh and Singapore and plans expansion into Indonesia, Bangkok, and Dubai in the coming months.

"My ambition is to stabilize in three or four markets before expanding further. Building a team is the priority for the next few years."

This suggests measured geographic expansion, proving the model in a handful of markets before attempting broader scaling. The company plans to eventually offer franchises, though all current outlets remain company-owned. Salman also mentions exploring "backward integration", owning manufacturing facilities rather than relying on third-party manufacturers.

Both moves would represent significant operational shifts. Franchising would mean giving up direct control for faster expansion with less capital. Backward integration would mean taking on manufacturing complexity for better quality control and margins.

The food-tech infrastructure Waffle Up is building, including POS systems, data analytics, and ordering platforms, becomes more valuable if Waffle Up can eventually franchise. These systems would allow maintaining quality control and capturing customer data even when outlets are franchisee-operated.

The strategic question for Waffle Up is whether the model can scale beyond 16 outlets while maintaining unit economics and brand coherence.

Waffle Up's bet: the dessert market is large enough, waffles are sufficiently unbranded at a global level, and the warehouse-to-outlet model can support rapid geographic expansion without massive capital investment per market.

The food-tech framing is central to this thesis. If Waffle Up is just another restaurant chain, it faces standard scaling challenges: high capital requirements per outlet, difficulty maintaining quality at scale, and dependence on local real estate markets. But if Waffle Up is a food-tech platform that happens to sell waffles, the scaling dynamics change.

The company faces several challenges. First, the virtual brand concept remains largely unproven at scale in food. While cloud kitchens and delivery-only brands have worked in some markets, few have built durable brand equity without physical flagship locations. Singapore currently has one Waffle Up outlet, but whether this validates Singaporean credentials in other markets is unclear.

Second, quality control in the warehouse-to-outlet model depends entirely on third-party manufacturers and individual outlet execution. This creates potential consistency issues as the company scales across countries with different supplier bases.

Third, the company competes for discretionary spending on desserts, a category that tends to be highly fragmented and localized. Building a global brand requires not just operational excellence but significant marketing investment to create brand awareness in new markets.

Fourth, even with selective capital raising, scaling will require substantial resources. The planned expansion into multiple Southeast Asian markets simultaneously will test whether the capital-efficient model can move fast enough to establish market position before better-funded competitors enter.

But Waffle Up has structural advantages that matter. Salman's restaurant background gives him operational instincts that pure tech founders lack; he knows what excellent food execution looks like and can identify when quality slips. "You have to understand the food." This operational expertise, the ability to taste a waffle and immediately know if the batter ratio is wrong, if the cooking temperature is off, if toppings are being applied incorrectly, is hard to replicate through systems alone.

The combination is rare: deep domain expertise in food operations, systems-driven thinking from tech entrepreneurship, and data infrastructure that compounds advantages over time. Most restaurant operators lack the technical sophistication to build the data and automation systems Waffle Up has created. Most tech entrepreneurs lack the food expertise to maintain quality at scale.

The company's architecture, Singapore brand anchor, Bangladesh execution base, warehouse-to-outlet model, and data-driven operations are designed specifically to solve the scaling challenges that have prevented global waffle brands from emerging. Whether that architecture proves sufficient depends on execution, but the strategic thinking is more sophisticated than most restaurant chains in similar markets.

At minimum, Waffle Up represents a test case for whether founders in emerging markets can build genuinely global consumer brands by combining local cost advantages with global brand positioning. More ambitiously, it tests whether the combination of deep food operations expertise and food-tech infrastructure can create a new category of scalable food brands, ones that maintain quality and brand consistency while avoiding the capital intensity of traditional restaurant chains.

Salman's conviction is clear: "We are in the early stages of learning to operate this way. But we have all the elements of a global brand."

The elements are there: proven unit economics, distinctive brand identity, scalable operational systems, expanding geographic footprint, and a founder who combines operator instincts with systems thinking. Whether those elements combine into the next Krispy Kreme or Domino's depends on execution. But the foundation is deliberate, the model is specific, and the ambition is backed by the rare combination of food expertise and technical infrastructure needed to achieve it.