Sharmin Kabir was in the 8th grade when she experienced menarche. No one had prepared her for it. Her family didn't discuss it. Her friends knew nothing about it, or if they did, she was too shy to ask. The experience was embarrassing, isolating, and utterly bewildering.

Sharmin was not an average student. She was the first girl in her class, a champion in sports, yet completely ignorant about herself, her body, and her physiological changes. She could solve complex problems but when mood swings inevitably happened on those difficult late afternoons and she asked her mother for help, her mom would give her 5 taka to buy some chocolates, as if that was the only remedy.

Her experience wasn't unique. Across Bangladesh, millions of girls navigate puberty and menstruation in a fog of shame and misinformation, their questions met with uncomfortable glances and whispered redirections. Even families who pride themselves on being modern and educated often stumble when it comes to discussing menstruation. The topic carries an almost supernatural weight of taboo; mothers speak in euphemisms, fathers avoid the subject entirely, and girls learn to hide what should be a natural part of growing up.

This cultural silence creates a dangerous vacuum where myths flourish and fear takes root. In rural areas, girls are sometimes told they're "unclean" during menstruation and forbidden from touching food or entering kitchens. Urban girls might escape the most extreme superstitions, but they still grow up believing their periods are something shameful to conceal.

The lack of proper education has cascading effects: nearly half of Bangladeshi girls miss school during menstruation, many using unsafe materials like old cloth or rags, and countless others develop preventable health complications from poor hygiene practices.

The consequences ripple far beyond individual discomfort. When girls consistently miss school, their academic performance suffers. When women grow up without understanding their reproductive health, they're more vulnerable to various reproductive health problems that could be prevented with proper knowledge and care. When half the population is taught to be ashamed of fundamental biological processes, society loses the full potential of its people.

"I felt completely alone and vulnerable," Sharmin recalls, her voice still carrying traces of that adolescent bewilderment. "Even in my rather progressive family, these topics were not in their awareness, which sometimes could be more dangerous than outright conservative attitudes."

But Sharmin's story didn't end with those frightening, chocolate-medicated afternoons in eighth grade. That moment of isolation and confusion became the seed of something transformative. That difficult childhood experience, that profound disconnect between her academic excellence and her complete ignorance about her biology, would eventually lead to her work.

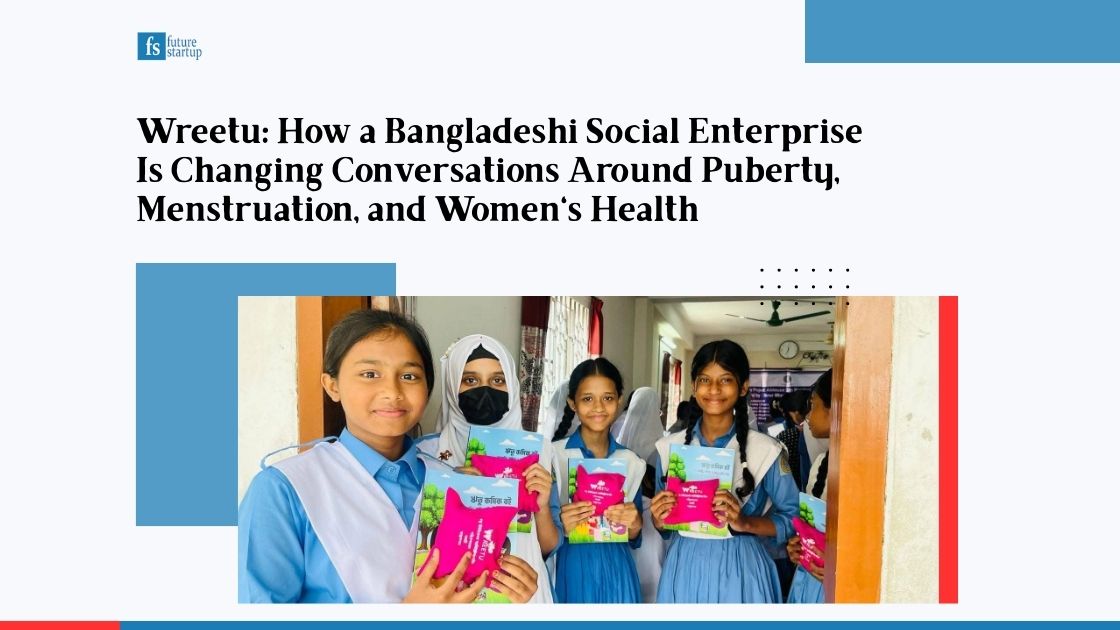

Today, she leads Wreetu, a social enterprise that has quietly changed how Bangladesh talks about puberty, menstruation, and sexual health. What began as one girl's determination to bridge the gap between academic achievement and basic self-knowledge has grown into a national movement reaching over 150,000 adolescents across 22 districts.

Through Wreetu, Sharmin has trained more than 600 educators, created culturally sensitive educational materials, and most importantly, given families the tools and courage to have conversations that were unthinkable just a generation ago.

Her journey from a confused teenager to a nationally recognized advocate for reproductive health illustrates something profound about social change: sometimes the most powerful movements begin when someone refuses to accept that excellence in every other area of life should coexist with ignorance about something so fundamental.

The genesis of Wreetu is rooted in Sharmin’s personal experiences and academic background. After studying English Linguistics and Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) at BRAC University, Sharmin seemed destined for the comfortable predictability of academic life. She worked with students on action research projects, finding satisfaction in the structured world of educational work. But her exposure to Bangladesh's emerging startup community ignited something within her, a growing sense that her real calling lay beyond university walls.

In May 2016, she made a decision that shocked her family and colleagues: she quit her job with just seven days' notice. The move seemed impulsive, even reckless, but it had been building for years.

As we described at the beginning of this story, the deepest motivation for Wreetu stemmed from her own bewildering experience with puberty. What haunted Sharmin wasn't just her memory of confusion and isolation, but the gradual realization that nothing had fundamentally changed in the years since. The same silence that had surrounded her eighth-grade experience was still suffocating girls across Bangladesh.

"When I looked around years later, nothing had changed," Sharmin says. "Girls in villages, girls in cities – they were all experiencing the same challenges I did. There was no way to marginalize."

This stark realization hit her with particular force when she learned that a significant percentage of reproductive health problems among Bangladeshi women are preventable with proper education and early detection. The connection was undeniable: the silence around menstruation wasn't just causing emotional trauma, it was killing women.

"I didn't wait for funding or perfect conditions," she explains. "I knew I had to start immediately."

Her initial thesis seemed deceptively simple: give girls the right information at the right time and build their confidence. But her approach was revolutionary in other ways.

While other organizations focused solely on girls, Sharmin insisted on including boys, fathers, teachers, and entire communities from day one in these conversations to create a supportive ecosystem. It was a decision that raised eyebrows and sparked resistance.

"People thought it was unnecessary," she remembers. "But I knew that without boys and men, any progress would be a myth."

This inclusion of men and boys was a "groundbreaking decision" for Wreetu, as historically, almost no other organization had undertaken such an initiative as early as 2015.

Sharmin believes that without actively engaging these male stakeholders, progress in girls' health and empowerment would be a myth. This has since influenced other major organizations to involve men and boys in their programs.

Wreetu's philosophy recognizes that a girl's confidence is not built in isolation; it comes within an environment where she feels understood and supported by everyone around her. When brothers understand why their sisters might need privacy, when fathers don't treat periods as shameful secrets, when male teachers can address the topic without embarrassment, girls begin to see their bodies as sources of strength rather than shame.

The organization's ultimate aim goes beyond education to something more fundamental: dismantling the deeply ingrained socio-cultural beliefs that turn female biology into a source of restriction and shame. It's about changing not just what people know, but how they think and feel about half the population's natural experiences.

Wreetu's first product was inspired by India's Menstrupedia, a comic book that explained puberty in an engaging and accessible way. But Sharmin wanted something uniquely Bangladeshi.

Thus, her team created the country's first illustrated storybook about periods. The book covered everything from basic biology to nutrition, from managing menstruation to when to see a doctor. The book has been translated into indigenous languages, like Chakma, to reach marginalized communities.

The book became a sensation. But it was just the beginning.

What started as a simple comic book evolved into a comprehensive ecosystem of products and services.

Wreetu's approach has evolved significantly since its inception, moving beyond just menstrual hygiene management to encompass a broader scope of reproductive health and girls' and women's health. We take a look at Wreetu’s core products and services below:

Awareness Workshops: Core to Wreetu's work, these workshops on puberty and menstruation are conducted across Bangladesh, often directly engaging students, parents, and teachers. They prioritize a human-centered, activity-based approach over mere lectures, ensuring deeper engagement.

Educational Materials:

Reusable Sanitary Napkins (2021): Wreetu began manufacturing reusable sanitary napkins to address issues of affordability, health, and environmental impact associated with commercial napkins. These are manufactured locally by underprivileged women, providing them with economic empowerment.

Community Support Systems:

Community-Based Projects

Community-Based Health Services (Comilla): In collaboration with Queens Commonwealth Trust, Wreetu conducts home-to-home visits in Comilla villages to address women's reproductive health issues and organizes mobile doctor services in local markets, making healthcare accessible to those who face financial and logistical barriers to reach district hospitals.

Climate Crisis Areas: Wreetu has expanded its work to climate-vulnerable areas like Barguna, Feni, and Nikli, where child marriage is prevalent, using interventions to foster gender equality and justice.

The Slum That Became a Village: Perhaps Wreetu's most ambitious project is transforming a Mirpur slum into what residents now call a village. The three-year initiative went beyond education to address infrastructure and dignity. The team renovated toilets and constructed shower places, installed electricity, and conducted regular awareness programs on period, dignity, and self-confidence. They trained men to understand and support women's needs. They created a sustainable model where families collectively maintain the improvements.

The project has led to significant improvements, with girls feeling comfortable inviting friends to the slum, improved marriage prospects, and women feeling safer changing menstrual products at night. School attendance increased. It follows a sustainable model where 10 families using a facility collectively pay for maintenance.

"We didn't just talk about periods," Sharmin explains. "We transformed an entire community's relationship with women's health."

Wreetu's journey has seen significant evolution and growth since its launch in late 2016. Initially, it focused primarily on awareness through workshops and the development of its comic book. The organization was propelled by small grants from accelerator programs like SPARK Bangladesh and Sharmin's personal savings. Sharmin emphasized that they did not wait for funding to begin; they started first and then figured things out.

A key organizational development was the separation into two distinct entities in 2021: Wreetu Health & Wellbeing Foundation (a registered not-for-profit) and a social enterprise (operating with a trade license).

This dual structure allows Wreetu to pursue both grant-funded impact projects and generate revenue through product sales, ensuring a path to long-term sustainability.

Each entity maintains separate legal, tax, and bank accounts.

"We had to be creative about sustainability," Sharmin explains. "We can't depend on grants forever."

Geographically, Wreetu has expanded its reach significantly. Initially operating in Dhaka, Kishoreganj, Rajshahi, Bogra, Natore, and Dinajpur, Wreetu now works across almost 22 districts in Bangladesh, with intense work currently in Kishoreganj, Gaibandha, Jashore, Faridpur, Patuakhali, Khulna, and Rangpur.

The organization operates with a lean core team of approximately nine full-time staff at its headquarters, complemented by a large network of over 400 contractual trainers and volunteers nationwide. These trainers are carefully selected and aligned with Wreetu's philosophy, ensuring sensitivity and cultural understanding.

Beyond menstruation, Wreetu's philosophical scope has broadened to address broader SRHR issues, technology-based solutions (like the 7teen online platform), climate vulnerability, and the overarching goal of gender equality and justice.

Wreetu's impact extends far beyond statistics, though the numbers are impressive. The deeper change, however, is cultural. Wreetu has helped shift menstruation from a source of shame to a topic of normal conversation. The organization has influenced policy discussions and inspired other organizations to adopt similar approaches.

"We've contributed to bringing periods into a positive narrative," Sharmin says. "That's something I'm incredibly proud of."

Wreetu's impact is evident across various layers of society.

Wreetu's programs have helped girls attend school during their periods, addressing the statistic that 44% of girls miss school due to menstruation. Schools are more ready to support girls, and boys offer support to girls in need.

Wreetu has been instrumental in normalizing discussions around menstruation, making it a positive narrative and bringing it into the mainstream consciousness. Fathers are now actively supporting their daughters. Boys openly deliver sanitary napkins, breaking deep-seated taboos. This collective shift in consciousness is a major contribution by Wreetu.

The "Transforming Slums into Villages" project has led to improved hygiene, safety (reducing incidents of assault), better community relations, and enhanced life prospects for women and girls.

In Comilla, where it runs a community-based project, women are now more willing to seek medical attention and discuss health issues with their families.

Wreetu's work challenges the historical societal perspective where "a girl being a girl was not good news" and aims to counteract the psychological impact of being shamed for natural bodily changes.

The organization has received grants from prestigious bodies like Queens Commonwealth Trust, Dutch Embassy, ShareNet International, Aqua For All, Manusher Jonno Foundation, WaterAid Bangladesh, and more, and recognition through awards such as the SOS Social Champion Award, Best Adolescents Experiences Leader by CEO Monthly, 2024.

Despite its success, Wreetu faces ongoing obstacles. Funding remains a constant concern. The organization sometimes struggles to reach the "right places" for networking and partnership opportunities.

"We often get projects through proposals rather than direct connections," Sharmin admits. "There's still a gap in awareness about our comprehensive work."

The challenge isn't just financial, it's about scaling impact while maintaining quality and cultural sensitivity.

But the work must continue.

Looking to the future, Wreetu harbors ambitious goals. Sharmin's ultimate goal is to work herself out of a job. She envisions a Bangladesh where reproductive health education is so normalized that organizations like Wreetu are no longer necessary, allowing Wreetu to shift its focus entirely.

"In 10-15 years, I want these issues to no longer exist in society," she says. "That's when we'll know we've succeeded."

A practical goal for the next decade is to train and empower a new generation of youth organizations to carry forward the work.

More immediately, Wreetu aims to achieve 50% financial sustainability by 2027, covering its operational costs through generated revenue from product sales.

The long-term vision extends beyond individual products to creating a comprehensive platform for girls' and women's health and becoming a one-stop resource for all necessary information, services, and products related to girls' and women's health. The organization plans to expand beyond menstruation to address pregnancy, menopause, and other aspects of girls' and women's health.

"We're not just selling books or napkins," Sharmin explains. "We're building a movement."

This movement includes advocacy for policy changes, leveraging its grassroots experience to influence national and international dialogue on gender equality.

Recognizing that menstrual stigma transcends national boundaries, Sharmin has increasingly carried Wreetu's message onto the global stage. What began as a movement to change conversations in Bangladeshi households has evolved into international advocacy that positions Bangladesh's experience as a model for other developing nations grappling with similar challenges.

In recent years, Sharmin has become a sought-after voice at major international forums, sharing not just Wreetu's innovations but the hard-won lessons from nearly a decade of grassroots work. Her keynote address at "Promoting Gender Equality through SRHR Education: Evidence from Bangladesh" during CSW68 at UN Headquarters in 2024 marked a significant moment, a Bangladeshi social entrepreneur presenting her country's homegrown solutions to a global audience hungry for practical approaches to menstrual health.

The invitations have multiplied as word of Wreetu's comprehensive approach spreads through international development circles. Sharmin has served as a panelist on critical discussions ranging from "Ending Period Poverty for South Asian Girls and Women" to "Youth-friendly Feminist Funding," both at CSW68, and "The Promise of Comprehensive SRHR towards achieving Beijing Platform of Action in Asia and the Pacific" at the Asia-Pacific Ministerial Conference in 2024. Each appearance reinforces a growing recognition that sustainable change requires the kind of community-wide approach Wreetu pioneered.

Wreetu's journey offers several insights for anyone attempting large-scale social change.

First, cultural transformation requires developing tacit knowledge that can't be easily codified or transferred. This means investing in apprenticeship-style learning rather than just formal training.

Second, successful social innovation often requires seeing systems rather than symptoms. The most effective interventions may be counterintuitive because they address root causes rather than immediate manifestations.

Third, feedback loops are crucial for developing expertise in cultural change. Organizations need mechanisms to sense how their interventions are working in practice, not just how they're intended to work.

Fourth, personal experience may be a critical component of expertise in social innovation. The ability to empathize with beneficiaries and understand their lived experience seems to inform more effective interventions.

Fifth, measurement in social innovation requires developing new metrics that capture transformation rather than just activity. This may require accepting some degree of uncertainty about outcomes.

When Sharmin Kabir founded Wreetu in 2016, she was attempting something that most development organizations struggle with: changing deeply embedded cultural norms at scale. The challenge wasn't just distributing information about menstruation and reproductive health; it was transforming centuries-old patterns of shame, silence, and superstition.

This is a classic problem of tacit knowledge. The expertise required to navigate cultural transformation cannot be easily codified into manuals or frameworks. It requires understanding subtle social dynamics, reading community resistance, timing interventions appropriately, and adapting approaches based on contextual feedback that's often unspoken.

Wreetu's nine-year journey offers a rare window into how such tacit knowledge develops and how it can be systematized without losing its effectiveness.

Today, Wreetu stands as more than a social enterprise. It's a testament to the power of turning personal pain into collective progress. By courageously addressing taboos, cultivating inclusive conversations, and providing practical solutions, the organization is building a more confident, healthy, and equitable future for girls and women.

The 8th-grade girl who once felt alone and ashamed has created a movement that ensures no other child has to experience that isolation. In a society where silence once reigned, Wreetu has sparked a conversation that's changing everything.

"We're not just talking about puberty," Sharmin says. "We're talking about dignity, equality, and the right of every girl to understand and embrace her body."

That conversation, once whispered in shame, now echoes across Bangladesh with the force of a movement.

Sharmin's story offers hard-won lessons for other social entrepreneurs.

Listen to your call. Most venture building is about listening to your deeper self, what Joseph Campbell called the Hero’s Journey. You hear a call from the inside to take on a mission, you listen to the call, and go on a journey. For Sharmin, Wreetu started as a call from the inside, which she decided to listen to.

Act with urgency. She regrets taking a year to publish her first book, emphasizing the importance of moving "as quickly as possible, with more force and speed."

Build capacity consistently. Organizational strength is crucial for long-term success.

Never compromise your vision. Even when advisors suggested simplifying her approach, Sharmin stuck to her comprehensive vision.

Ideas matter more than gender. Sharmin has never let being a woman limit her ambitions or serve as an excuse for setbacks.

Wreetu Founder Sharmin Kabir was interviewed for this article.