A draft law responding to fraud cases includes necessary reforms—but also an ownership restriction that will stifle the growth of the sector and contradict Bangladesh's economic priorities.

Bangladesh's travel agency sector faces some serious challenges. In recent years, several offline and online travel agencies have been involved in fraud cases. Customers lost money on tickets that were never delivered. Agencies collapsed, leaving both smaller B2B agencies and travelers stranded. Trust in the industry eroded.

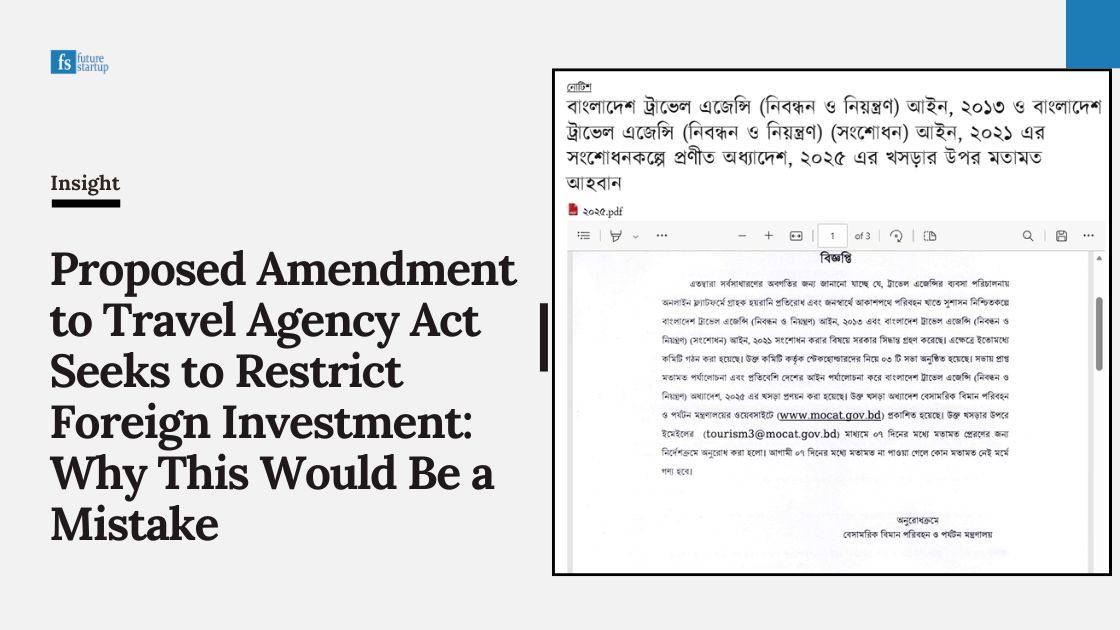

The government's response is overdue. On October 29th, 2025, the Ministry of Civil Aviation and Tourism published a draft amendment to the Bangladesh Travel Agency Act to strengthen regulation. According to the ministry, the changes are needed "to prevent customer harassment on online and offline platforms" and "to ensure good governance in air travel." The ministry is seeking public feedback within seven days by emailing tourism3@mocat.gov.bd.

The draft addresses real concerns. It raises capital requirements. It imposes stricter penalties. It mandates better technology and compliance systems. These reforms are necessary and welcome.

But buried in the technical language is a provision that has nothing to do with preventing fraud: travel agencies must have 100% Bangladeshi ownership. No foreign investment would be permitted.

This restriction threatens to undo years of progress in digitalizing the sector and limit its growth and potential. It runs counter to Bangladesh's push for foreign investment. And it solves none of the problems that prompted these amendments.

Let’s take a look at the proposed amendments first. The Bangladesh Travel Agency (Licensing and Regulation) (Amendment) Act, 2025, seeks to make several changes to the 2013 law and its 2021 amendment. Some of the proposed amendmends are:

On capital requirements: The draft establishes license categories with minimum capital requirements. Domestic agencies need 10 lakh taka. International agencies need 1 crore taka. These increases are designed to ensure agencies have financial buffers.

On penalties: The draft increases maximum punishment from six months imprisonment or a 5 lakh taka fine to three years imprisonment or a 50 lakh taka fine. That is a tenfold increase, clearly intended to deter fraud.

On compliance: Agencies must obtain Criminal Investigation Bureau (CIB) clearance. They cannot be loan defaulters. They need government approval before starting new business activities. These provisions screen out problematic operators.

On technology: The draft mandates that agencies use Global Distribution Systems (GDS) and New Distribution Capability (NDC) platforms. They must maintain digital records and adopt e-commerce systems. The law pushes digitalization and creates audit trails.

On ownership: The draft amends Section 6(ক), adding new language after "is not a citizen of Bangladesh." The addition reads: "or in case of partnerships and limited companies, does not have 100% Bangladeshi ownership." Foreign investors cannot own any stake in a Bangladeshi travel agency. Not a majority. Not a minority. Nothing.

The first four categories of changes make sense. They directly address the fraud problem. The ownership restriction does not.

Consider the facts: the travel agencies involved in recent fraud cases were fully Bangladeshi-owned. Flight Expert was Bangladeshi-owned. Travel Business Portal was Bangladeshi-owned. Fly Far International was Bangladeshi-owned. Local ownership did not prevent fraud.

Meanwhile, foreign-invested platforms like GoZayaan and ShareTrip have operated without major fraud incidents. According to industry data, these platforms have collectively served over 3 million Bangladeshi travelers. They brought transparent pricing, verified booking systems, and consumer protection mechanisms that many traditional agencies lacked. It means the fraud incidents have nothing to do with the ownership model.

On the other hand, foreign capital can play a significant role in helping the sector grow and modernize. Foreign capital not only brings the necessary capital required to build a scalable business but also brings expertise that can help local companies serve customers better and expand outside Bangladesh. Contrarily, banning foreign investment to prevent fraud makes no logical sense. It will only limit the potential and growth of the sector, stifle competition and innovation, and deprive customers of better options in the market.

This creates an immediate contradiction. The interim government has made attracting foreign investment a priority. Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA) actively courts international capital. Startup Bangladesh, launched with government support, aims to build a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem with global participation.

While BIDA works to open doors for global partnerships, this policy would shut them. You cannot welcome foreign investment while simultaneously banning it in specific sectors without a clear justification.

GoZayaan and ShareTrip have raised over $20 million in foreign direct investment from Singapore, Japan, Southeast Asia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. This capital came with global expertise, technology platforms, and employment opportunities. The ownership restriction would end this model entirely.

Existing companies with foreign investment would face an impossible choice: divest completely or cease operations. New foreign investment would be prohibited. The global partnerships that enabled digitalization would terminate.

Bangladesh is scheduled to graduate from Least Developed Country (LDC) status in November 2026. This transition requires the country to become more competitive and open to international trade and investment.

As Bangladesh prepares for graduation, the global expectation is that it will reduce trade barriers and align policies with international standards. Moving in the opposite direction—by imposing new sector-specific restrictions on foreign investment—sends exactly the wrong signal at exactly the wrong time.

Countries graduating from LDC status typically liberalize investment rules, not restrict them.

Bangladesh's neighbors have moved in the opposite direction. Regionally, many countries allow substantial foreign investment in travel agencies. India, Vietnam, Thailand, and others permit the majority or full foreign ownership. Sri Lanka, despite the economic crisis, actively seeks foreign investment in tourism. The Maldives, whose economy depends on tourism, welcomes foreign capital. Indonesia allows foreign ownership in travel agencies. Bangladesh would become an outlier if it moves toward complete restriction while its neighbors liberalize.

When regional competitors actively court investment, Bangladesh's isolation carries real costs. Investors compare regulatory environments. They choose destinations with stable, predictable rules.

The draft mandates that agencies use GDS and NDC platforms—sophisticated systems requiring expertise, ongoing support, and global integration. Foreign partners typically come with expertise that can help the sector advance. Higher capitalization requirements mean agencies need access to capital. Foreign investment is one source. Digitalization requires technology capabilities. Global firms excel at this.

You cannot mandate modernization while banning those best equipped to deliver it. If the goal is preventing fraud, the solution is stronger oversight: regular audits, consumer protection insurance, customer complaint mechanisms, and swift enforcement. These measures work regardless of ownership structure.

This reflects unnecessary regulatory capture in our policy landscape that favors the incumbents in many sectors. Industry sources suggest the ownership restriction clause reflects lobbying by traditional travel agencies. The irony is sharp. Several travel agencies that failed were fully Bangladeshi-owned agencies. Their business problems stemmed from their inability to operate effectively as businesses, not foreign ownership.

For years, Bangladesh's travel industry operated with limited regulation. Traditional agencies dominated through opaque commission systems and middleman networks—a syndicate-driven structure benefiting incumbents while depriving consumers of better services. Many digital platforms helped change this with transparent pricing, online payment systems, and verified bookings. Now, many incumbents want protection from competition. The ownership restriction provides it.

Restricting foreign investment will not only be an anti-competitive move, but it will only serve the incumbents while depriving customers of more and better options and better services, which should not be the role of any policy that aims to ensure consumer safety.

The impact extends beyond travel. Many institutions that invested in GoZayaan and ShareTrip also back Bangladesh's fintech, e-commerce, and technology ecosystems. Venture capital firms make portfolio decisions holistically. A hostile policy in one sector can affect their view of the entire market.

Venture capital firms from Singapore, Japan, and other regional funds that have supported Bangladeshi startups will reassess risk. If the government can unilaterally ban foreign ownership in travel, what prevents similar moves in fintech? In e-commerce? In logistics?

Policy uncertainty deters investment. The message extends far beyond travel agencies.

Moreover, the ownership restriction may conflict with Bangladesh's investment commitments. Legal experts note that revoking or conditioning existing licenses based on ownership could expose Bangladesh to international arbitration claims—creating unnecessary legal and reputational risk.

The ministry's concerns about consumer protection, financial stability, and regulatory compliance are legitimate. The fraud cases that prompted these amendments harmed real people. Stronger regulation is necessary.

To that end, most of this draft is sound. Higher capital requirements, CIB clearance, loan defaulter bans, technology mandates, and increased penalties all address the problems that occurred. They should be enacted.

The ownership restriction should be withdrawn. It does not address fraud. It runs counter to national economic policy. It contradicts Bangladesh's LDC graduation trajectory. It isolates the Bangladesh regionally. It threatens the growth of the sector. And it signals unpredictability to investors across all industries.

If the government insists on ownership restrictions, it should follow regional practice. A 51% local ownership requirement would maintain local control while allowing foreign participation and technology transfer. But even this would be unnecessary given the other protections in the draft.

The consultation period should be extended. Seven days is insufficient for stakeholders to analyze a complex draft with major economic implications. Thirty days would be standard international practice for legislation of this significance.

BIDA and the interim government's economic reform team should review the draft. The contradiction between this policy and Bangladesh's investment promotion efforts needs resolution at the highest level. Different ministries cannot work at cross purposes.

The travel agency sector is a multi-billion-dollar industry that contributes significantly to national revenue, employment, and global connectivity. Policy signals matter. Investors watch how governments treat existing commitments. They notice when regulations suddenly favor incumbents over innovators. They remember when countries that invited them in later showed them the door.

Bangladesh has worked to build credibility as an investment destination. This draft threatens that credibility. The ministry has an opportunity to strengthen regulation without undermining investment. It should separate the sound provisions from the harmful ones, enact the former, and discard the latter.

Public feedback can be submitted within seven days via email to tourism3@mocat.gov.bd or through the ministry website at www.mocat.gov.bd.