Bangladesh Bank has introduced a new foreign remittance facility for small and medium enterprises. SMEs can now remit up to $3,000 annually for business expenses abroad. They can use bank transfers or special SME Cards with $600 limits. But there's a catch: SMEs must register with the SME Foundation to qualify.

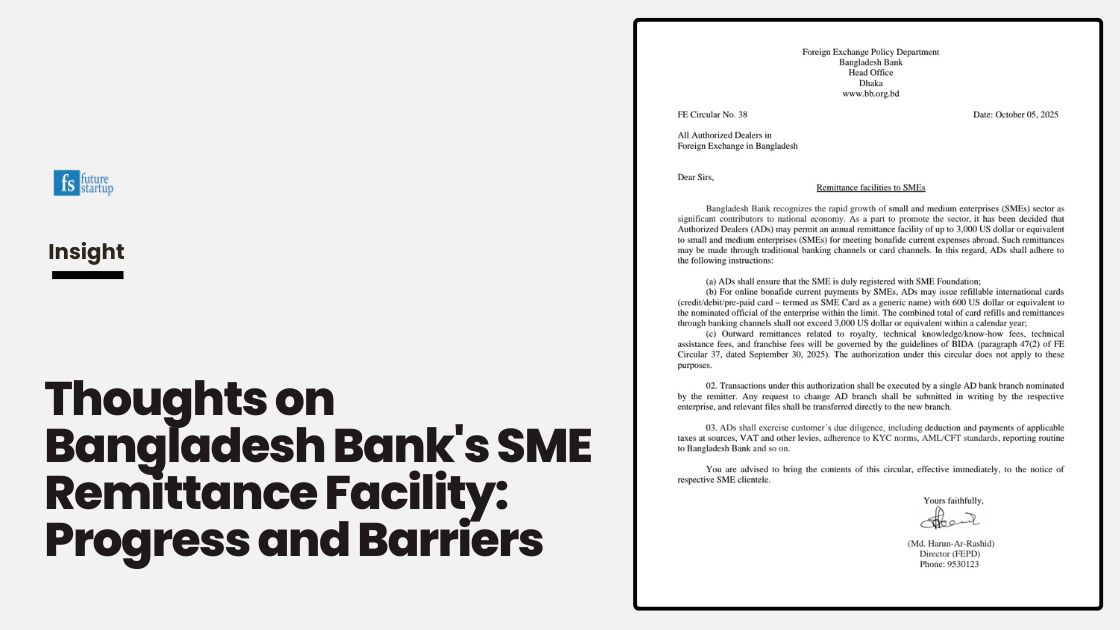

The circular, FEPD Circular No. 38, took effect on October 5, 2025. It provides a structured path for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) to access foreign exchange for international business expenses. It covers routine business expenses but excludes royalty payments and technical fees, which fall under separate BIDA guidelines.

Policies are complex affairs. When you are putting forward a policy decision, you’re not only looking to advance the good and maximize the upsides. You’re equally looking to minimize the downsides and limit unwanted outcomes. This complexity makes it difficult to write about policy decisions. But policies are critical. They come with real costs. Every policy decision has both immediate and long-term consequences. Good intentions are rarely enough. Often, no policy is better than a bad policy. As such, they should be scrutinized.

So, in this article, I try to understand the implications of this one—what it means for the SMEs, how to think about the policy, and what could have been better.

First, an overview of the circular.

Key Provisions Breakdown

The circular grants registered SMEs an annual remittance facility of up to $3,000 to cover "bonafide current expenses abroad." This includes payments for services, software, digital advertising, and professional fees. A key innovation is the introduction of a dedicated SME Card—a refillable international credit, debit, or pre-paid card with a sub-limit of $600 specifically for online payments.

However, this facility is not a free-for-all. It is tightly regulated:

Let’s take a deeper look.

Bangladesh Bank deserves credit for recognizing that SMEs need an outward remittance facility and taking an initiative to give them a legal channel to do so. In a country where capital controls remain tight and forex access has historically been reserved for large corporations and exporters, extending facilities to SMEs represents meaningful policy evolution.

The card-based payment system deserves particular mention. Many SMEs in Bangladesh struggle with traditional banking formalities—extensive documentation, multiple approval layers. A pre-paid card with a $600 limit eases access.

By capping individual cards at $600 while maintaining a $3,000 total ceiling for all remittances, Bangladesh Bank prevents system gaming. You can't simply issue five cards and move $3,000 through cards alone. The design forces aggregate control.

Context partly explains the total ceiling here. Bangladesh has faced forex pressures in recent years. The taka depreciated significantly against the dollar in 2022-2023. In this environment, being cautious about capital outflows can be explained as prudent macroeconomic management. But the ceiling appears to be too low compared to many Bangladesh’s peers.

The facility addresses real business needs. For thousands of small businesses operating at the margins of the formal economy, this opens doors that were previously shut. Bangladesh's SME sector is growing rapidly and increasingly integrated with global markets. These businesses need forex access to grow. This circular, however modest, provides it. It addresses a major operational hurdle for SMEs, allowing them to easily pay for essential international services.

It brings a previously complex or informal process into a regulated, transparent framework, reducing the temptation to use unofficial channels (hundi). Finally, by setting clear limits and procedures, the circular reduces ambiguity for both banks and SMEs, potentially speeding up transaction times.

The SME Foundation registration requirement appears to be one of the key flaws. It adds bureaucratic friction precisely where policy should reduce it.

Every business in Bangladesh already has:

Now they need SME Foundation registration too. This layering can be costly for both businesses and the government.

The question isn't whether gatekeeping serves some purpose. It might. The question is whether this particular gatekeeper is necessary given existing mechanisms. And the answer is almost certainly no.

Trade licenses already identify legitimate businesses. Tax registration proves businesses are in the formal economy. Bank KYC processes verify identity and screen for money laundering risks. What additional value does SME Foundation registration provide? The circular doesn't explain.

Regional peers demonstrate different approaches. India's approach under the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) is instructive. Under FEMA, the general principle is that all current account transactions are permitted unless expressly prohibited, while all capital account transactions are prohibited unless expressly permitted. For business payments—such as software subscriptions, marketing expenses, and professional services—Indian companies can make payments through authorized dealer banks based on standard documentation. No separate SME registration is required.

India does have the Liberalised Remittance Scheme (LRS), which allows resident individuals to remit up to $250,000 annually for both current and capital account transactions. While this is technically for individuals, it illustrates India's more permissive philosophy toward forex access. The emphasis is on banking sector compliance rather than additional government registrations.

Pakistan's Foreign Exchange Manual similarly places responsibility on authorized dealer banks to verify documentation—business registration, National Tax Number (NTN), and transaction-specific documents like invoices. The State Bank has progressively liberalized business remittances; in 2021, it doubled limits for digital service providers to $400,000 annually, recognizing the needs of Pakistan's growing IT sector. No separate SME development agency acts as a mandatory checkpoint for routine business payments.

Sri Lanka presents a more complex picture. Following its severe 2022 forex crisis, the Central Bank imposed strict controls. However, even under these emergency measures, the approach has been to work through the banking system. Current regulations (as of June 2025) show that companies incorporated in Sri Lanka can remit through Business Foreign Currency Accounts for 'expansion of business overseas' up to $200,000, while personal foreign currency accounts held by Sri Lankan residents allow remittances limited to $20,000. These limits vary by investor type and purpose, but the framework still doesn't require a separate SME Foundation-type registration.

The pattern across the region: successful forex management happens through banking sector compliance, not parallel bureaucracies.

That said, perhaps Bangladesh Bank has reasons for caution that aren't immediately obvious. Maybe previous experience showed banking due diligence alone was insufficient. Maybe tax records in Bangladesh are less reliable than in neighboring countries. Maybe there's a formalization objective—bringing informal SMEs into the registered economy by creating incentives for registration.

A Trade License or general Business Registration (e.g., from RJSC) only confirms that a business is legal. It does not verify its status as an SME. The SME Foundation registration acts as a filter to ensure the scheme benefits its intended recipients and not larger corporations or shell companies. This is fundamental to targeted industrial policy. For the government and Bangladesh Bank, this registration can be a vital source of data, allowing them to track uptake, measure impact, and inform future policy.

Finally, for the banks and Bangladesh Bank, concentrating this new forex facility through a verified list simplifies AML/CFT checks. It adds an additional layer of scrutiny beyond the bank's standard KYC, reducing the risk of the facility being misused for illicit capital flight.

The philosophy is not to use a general business license but to have a specific certification for targeted benefits.

Even if we consider the SME Foundation registration a necessary evil, its implementation will determine whether it is a useful filter or a barrier.

The process should be made entirely online, seamless, and linked with the National Board of Revenue (NBR) and RJSC for automatic data verification. The application should be a simple form declaring turnover, employee count, and asset value, with a random audit process for compliance, rather than pre-approval of every document.

If the SME Foundation registration serves a broader developmental purpose—connecting businesses to financing, training, support services—then forex access becomes one benefit among many. The Foundation isn't just a gatekeeper; it's an ecosystem builder.

But this requires the Foundation to actually deliver these services efficiently, for which we have to wait and we have every right to be skeptical.

Administrative burden and red tape. This is the most significant challenge. For an SME owner, navigating a new government registration process can be daunting, time-consuming, and perceived as just another piece of bureaucracy. This can deter eligible businesses from availing the benefit, defeating the policy's purpose.

Cost of compliance. While the registration fee itself might be low, the opportunity cost is high. The business owner or a staff member must spend valuable time (often during business hours) gathering documents, filling out forms, and potentially making multiple visits to offices. For a very small enterprise, this lost time directly impacts productivity and revenue.

Government costs and implementation capacity. Maintaining the registration system, processing applications, and verifying data requires a dedicated government apparatus. This involves staffing, IT systems, and operational costs. If the process is inefficient, it becomes a drain on public resources.

India avoided this trap by keeping forex access separate from developmental programming. The MSME registration portal (Udyam) offers benefits like easier credit access and government procurement preferences—but it's not mandatory for basic foreign exchange services.

Enforcement complexity multiplies. Banks must verify SME Foundation registration for every transaction. What happens when registrations lapse? How frequently must SMEs renew? Can the Foundation handle queries from dozens of banks? When rules are clear and verification mechanisms are straightforward, enforcement happens efficiently. When rules require coordination across multiple agencies, compliance costs increase and effectiveness declines.

The exclusion list creates confusion. Royalty payments, technical fees, and franchise fees fall under separate BIDA guidelines. But distinguishing between "bonafide current expenses" and "technical knowledge fees" is often ambiguous. Is payment for Salesforce a software subscription (permitted) or a licensing fee (excluded)? Is consultant payment for implementation assistance a current expense or technical knowledge transfer? Ambiguous categories create friction that harms everyone, even when intentions are good.

Corruption risk increases, but so might formalization benefits. Every new registration requirement creates opportunities for rent-seeking. Transparency International Bangladesh reports consistently highlight how registration processes become extraction points. Adding the SME Foundation as a mandatory checkpoint introduces vulnerability.

But there's a counterargument: perhaps formalization benefits outweigh corruption risks. If SME Foundation registration brings informal businesses into the visible economy, tax collection improves, data quality increases, and policy becomes better informed. The question is whether these benefits materialize in practice.

To counter potential extraction risk, Bangladesh Bank could mandate digital-only registration with clear timelines and automated approvals where criteria are met.

Option 1: Adopt a banking-centric verification model. Rather than creating a new registration requirement, Bangladesh Bank could place responsibility on authorized dealer banks. Banks already perform extensive KYC, monitor transactions for AML/CFT compliance, and report suspicious activities.

Bangladesh Bank could require banks to:

This distributes the compliance burden across the banking system rather than concentrating it in a single, potentially under-resourced agency or the SME businesses. Banks have strong incentives to get it right given their regulatory requirements.

Option 2: Trust existing documentation with enhanced monitoring. Banks could verify trade licenses, TIN certificates, and business registration before processing SME remittances. Add transaction-specific documentation (invoice, contract, payment agreement) and require banks to retain records. This approach leverages infrastructure that already exists. Every SME getting the forex facility already has a bank relationship. The bank already has KYC documentation. Why create a parallel verification system?

Option 3: Make SME Foundation registration genuinely digital and instantaneous. If registration is deemed necessary, make it frictionless. An SME owner enters their business registration number; the system automatically pulls trade license data from city corporations, tax records from NBR, and bank information from KYC databases. Registration completes in minutes, not weeks.

India's Udyam portal shows South Asian feasibility. Enter your Aadhaar number and business details; the system validates against GST and PAN databases automatically. Bangladesh could replicate this architecture, linking SME Foundation registration with existing government databases.

Option 4: Graduated limits based on business track record. Rather than a flat limit, implement risk-based thresholds. Start with $3,000 for businesses in their first year, increasing gradually based on clean tax records, compliance history and age and the size of businesses. This balances caution with recognition that older businesses with proven track records pose lower risk.

Option 5: Build in a sunset clause and mandatory review. The circular could include a provision requiring Bangladesh Bank to review the policy after 18-24 months. Mandate collection of data on: utilization rates (how many SMEs are using the facility?), processing times (how long does SME Foundation registration take?), compliance costs (what are banks spending on verification?) and abuse incidents (are there problems with misuse?)

If the SME Foundation becomes a bottleneck, switch to banking-centric verification. If specific exclusions are causing disputes, clarify them.

Build learning into policy design from the start. Policy shouldn't be set in stone—it should evolve based on evidence.

This circular reflects Bangladesh's ongoing tension between economic liberalization and capital control. The country maintains a managed float exchange rate regime with significant central bank intervention. Capital controls are tools for managing this regime.

India liberalized its foreign exchange regime progressively after 1991, with FEMA replacing the more restrictive FERA in 1999, representing a philosophical shift from "everything prohibited unless permitted" to "everything permitted unless prohibited." The Liberalised Remittance Scheme, introduced in 2004 and expanded over time, exemplifies this approach. Current account transactions for businesses face minimal restrictions beyond banking due diligence.

Pakistan followed a similar but slower trajectory.

Sri Lanka's experience is cautionary. The country maintained relatively liberal foreign exchange rules until the 2022 crisis. When reserves depleted catastrophically, the Central Bank imposed emergency restrictions. Sri Lanka is gradually unwinding these restrictions, but the crisis demonstrated how quickly liberal regimes can reverse when reserves vanish.

The lesson: capital controls are like antibiotics. Use them carefully, minimally, and temporarily. Overuse breeds resistance and unintended consequences.

Bangladesh's approach reflects this lesson. The country is liberalizing gradually, testing capacity at each step, monitoring for abuse, adjusting as needed. The $3,000 SME facility is one step in a longer journey toward a more open forex regime.

Outward remittances for business purposes remain small—a reflection of both limited need (most SMEs are domestic-focused) and limited access (forex constraints). As the economy diversifies toward services and higher-value manufacturing, outward remittances will need to grow. Policy must accommodate this.

This circular contributes to that support structure. It's imperfect, constrained, and perhaps over-bureaucratized. But it exists, which is better than nothing.

Direct numerical comparisons between countries are difficult because regulatory frameworks differ significantly in structure and philosophy. However, we can compare approaches:

India (FEMA Framework)

Pakistan (Foreign Exchange Manual)

Sri Lanka (Post-Crisis Controls)

Bangladesh (New SME Facility)

Bangladesh's approach adds more process layers than its regional peers. Whether this reflects necessary caution or excessive conservatism depends on how you look at it and the state of the political economy in the country.

FE Circular No. 38 expands SME access to foreign exchange—that's genuinely positive. The card-based system shows user-centric thinking. The combined limit structure demonstrates sophisticated thinking. In a country where capital controls remain tight, this circular represents meaningful liberalization.

But the SME Foundation registration requirement is a potential misstep. It adds costs, creates bottlenecks, and misses the opportunity to leverage existing documentation and banking infrastructure. Regional peers demonstrate that simpler approaches work better—though to be fair, they also have different economic contexts and longer liberalization histories.

Yet criticism must acknowledge context. Bangladesh Bank is managing legitimate concerns about capital flight. The country is liberalizing gradually, building capacity at each step. This circular represents one step in a multi-decade journey.

While other countries offer lessons, every policy evolution takes time.

If this circular proves one thing, it's that policy evolution requires learning. Bangladesh Bank should monitor implementation closely. Track registration processing times. Measure transaction volumes. Survey SME satisfaction. Identify bottlenecks. Document abuse cases, if any. Then revise.

The ideal next iteration: After 18-24 months, issue a revised circular based on these learnings. Keep what works (the card system is genuinely good). Drop what doesn't (bureaucratic friction without commensurate benefit).

Sometimes the best policy is less policy. But sometimes policy has to exist, and when it does, it should be as simple and effective as possible.

Bangladesh's SME sector is growing rapidly. Digital exports are expanding. Service-based businesses are integrating into global markets. Policy must support this transformation while managing legitimate macroeconomic risks. This circular attempts that balance.

Progress is rarely elegant. It's messy, incremental, and often frustrating. Policy gets made under constraints—political, economic, institutional—that outside critics don't always appreciate. The question isn't whether a policy decision is perfect. It's whether it moves in the right direction and creates space for learning and improvement.

Bangladesh Bank has taken a step. The true test, however, lies ahead. If the government can simplify the registration gateway and banks can implement it seamlessly, this policy has the potential to significantly empower a generation of Bangladeshi SMEs. If the bureaucratic hurdles remain high, it risks being a well-designed policy that never quite delivers on its promise.