Kamal Uddin Gazi Jishan is the co-founder of Qormotho Limited, a finance and accounting outsourcing company that has built a fascinating global business from Bangladesh within a short time. Before Qormotho, Jishan built an impressive international career. He taught ACCA in Dhaka, studied advanced accounting at Kaplan Financial in London, worked as an internal auditor at BRAC, and eventually became Head of Internal Audit for a multi-billion dollar conglomerate in Qatar.

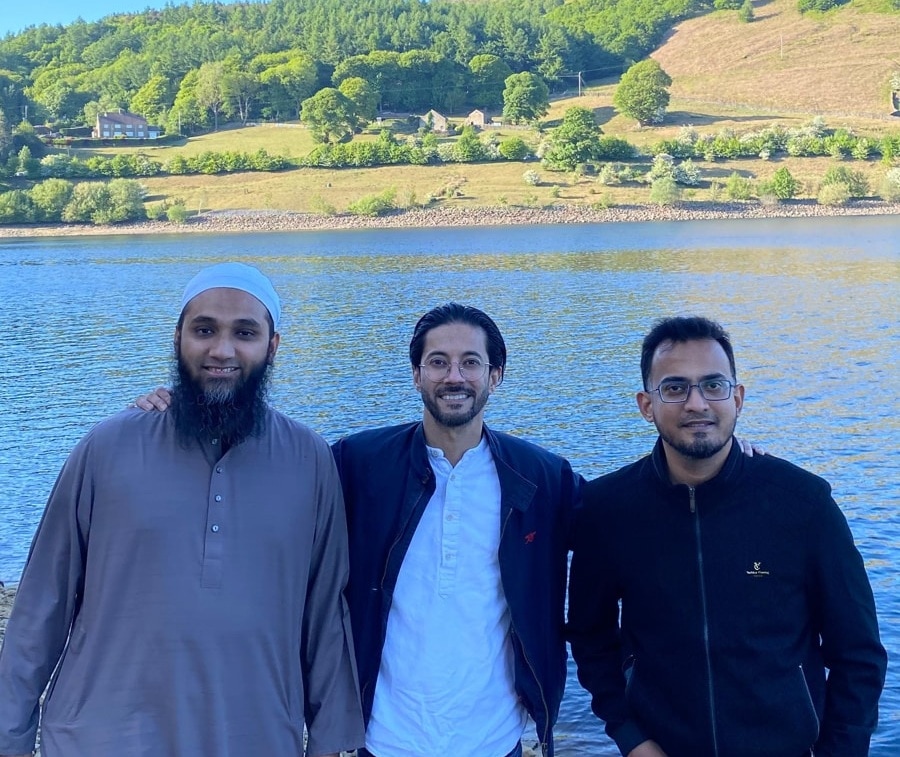

Qormotho, founded by Mr. Jishan and his two friends Asad Akber, and Ahmad Hamid, started as a small side project. The founders initially did it as an experiment, working part time on the side of their full-time jobs. The company has since outgrown into a full-fledged BPO company and the three founders have moved full time to expand the business. Today, Qormotho has clients across USA, Europe, Asia, and Middle East and is a team of 55 professionals.

What makes Mr. Jishan's story particularly fascinating is his unconventional path. His journey from accounting lecturer to entrepreneur spans multiple countries, offering rare insights into building a global career from Bangladesh.

In this conversation, we talk about Mr. Jishan’s journey, his decision to leave a seven-figure salary to go full-time with Qormotho, discuss the art of managing remote teams, building trust, creating systems when traditional management fails, and his lessons from building an international career and building a global service company. We examine Qormotho’s growth and its plans to position Bangladesh as a premier destination for finance and accounting outsourcing. Mr. Jishan shares insights on delegation, attitude, humility, authenticity, and what he calls "farming versus hunting" in business development.

The interview shows how professional training can become a foundation for entrepreneurial success. Jishan's experience in internal auditing—questioning assumptions, building stakeholder relationships, thinking about risk and opportunity—translated directly into his company-building approach.

There are deeper philosophical threads throughout. We talk about the importance of being relevant in your field, the power of listening, and his framework for building successful partnerships.

For anyone building a service business or thinking about global expansion from Bangladesh, this conversation offers both practical frameworks and philosophical guidance. Enjoy!

Mohammad Ruhul Kader: Thank you so much for agreeing to do this. Let's start by talking about yourself, your background, where you come from, and your path to what you're doing today.

Kamal Uddin Gazi Jishan: Thank you for having me. It's a pleasure to share my personal journey. My name is Kamal Uddin Gazi Jishan, though I go by Gazi Jishan nowadays on my marketing platforms to keep it simple and concrete.

I'm a chartered accountant first and foremost. My career kicked off as an accounting lecturer which I did part-time for many years. On a corporate level, I transformed into an internal auditor role after an initial few years in accounting. Side by side, I was—and continue to be—a business owner of an outsourcing company.

You could say I'm an accountant who transformed into an auditor and then moved into entrepreneurship. Alhamdulillah, right now my entrepreneurial journey has kicked off fully as Qormotho has unfolded.

Ruhul: Where did you grow up? Tell us about your schools and education, and any formative experiences in those early years that shaped your outlook about the world.

Gazi Jishan: My early days were spent growing up in Dhaka. I was born in Green Road and grew up in Dhanmondi, going to an English medium curriculum school.

At home, my mother was an entrepreneur. My mother used to train women on various skills such as boutique work, cooking, being independent, and so on. I grew up in that environment, and as I grew up, I used to contribute to my mother's business. I would come back from school and be the cashier and the computer operator. I received my first work experience letter at the age of 12.

I chose accounting as my subject because my parents, particularly my father, encouraged me toward that. He would come home and tell me good things about what a chartered accountant career looks like—that it's a prestigious qualification, a very privileged career, etc. He also did something very unique: he printed a few bold stickers that had printed "I am a chartered accountant" and pasted them around my room. He used to tell me to visualize this everyday.

In many ways, he influenced me. That's how I started my accounting education.

Ruhul: It would be great if you could touch on your education and what happened after that, your time in Bangladesh, moving to the UK for further education, returning to Bangladesh, and eventually moving to Qatar. It would be great if we could tie all these different aspects of your journey together.

Gazi Jishan: I'll try to go phase by phase. My beginning was choosing accounting in Bangladesh. I chose ACCA. ACCA is a global qualification, which was intriguing to me because I would get a globally recognized qualification.

I chose ACCA over other available degrees also because it had a fast-track curriculum. I went directly from A-levels to ACCA. That fast track actually helped me, because nowadays employers value professional skills over degrees.

When I started ACCA, I was very quick to complete my fundamental modules. I was ahead of my peers and was a good student, passing exams on first attempts. As a result, the managing director of the institute where I was studying in Dhanmondi, Dhaka offered me a position to teach a fundamental subject there, to become a tutor.

That was my first job as an accounting lecturer. I had my first printed business card. I had completed the foundation level and was studying on the intermediate level, but I was also teaching the foundation level subject. I used to enjoy teaching, the classroom environment, and helping other accounting students to prepare and pass ACCA exams.

Soon after, I decided to move to get the best quality tuition, which was available in the UK. I went to London to study the remaining parts of ACCA with Kaplan Financial. This helped me get the highest quality education and training available.

I passed my ACCA—well, all subjects I passed within three years, but one subject I got stuck on. That one subject went on for another three years, which was very testing for me.

That's another part of the story. I came back from the UK with one subject remaining. That subject was Advanced Performance Management, and any ACCA student will recognize this. I had to be persistent with that subject. Once I failed the first time, I felt like I had to pass it. The second attempt, I failed again.

In ACCA, you had the option to switch to another subject like Tax or Financial Management—but for me, I decided I would not change. I became very stubborn and kept taking the exam. I was determined not to change. It would be like giving up. I wanted to keep trying to pass and prove to myself that I could do it.

But the timing was not easy for me. I was entering my career. My family was gradually starting to depend on me. So it was tough, because I was no longer a full-time student. It took me three more years to pass one subject. That's how I finished ACCA.

I was by that time back in Bangladesh. I joined an accounting firm called Acnabin, a very reputed and well-established firm.

I started on simple terms with a simple job profile and almost negligible income, but the experience was very helpful. That was my return from the UK, continuing or starting my proper professional career. Side by side, when I came back, I also continued teaching advanced ACCA subjects part-time, because I was well-trained in the UK. So I carried all those notes and training methods back to Bangladesh.

Ruhul: Please tell us more about this period of three years that it took you to pass Advanced Performance Management? How did you deal with that period? I assume it was difficult.

Gazi Jishan: Yes, it was. I dealt with it this way: Exams happened every six months, and I attempted every time. In three years, I attempted every time, which means I took seven attempts to pass that one exam. I don't feel any hesitation about it—even at that time I didn't—but there was some self-doubt, some pressure, fear of failing other’s expectations of me.

So what I did was: one, I gave exams consistently and persistently. I didn't skip—I didn't take a break from studying for one year or two semesters. Every six months, I went for exams.

Number two, I was self-studying and always trying to prepare. In the advanced stage, it's more practical than theoretical, so I was trying to relate my workplace knowledge and bring it into the classroom. I was trying to build my knowledge and make it relevant. I was taking help from online resources because at that time there was no proper guide available in Bangladesh to join, or I wasn't finding any circle to join because I had already exceeded or gone ahead. I didn't have any friend circle for studying or a study partner. So I was relying on my own self-study plus online resources.

The final bit was that I used to test myself in the exam. In one exam, this happened: I went to the exam and the question pattern was 50 marks, 25, 25, and you had to choose two questions from three or four options. I opened the exam paper and saw that the 50-mark question was something I was familiar with, but the remaining options in Section B were completely out of my bounds. They were too difficult, and the concepts weren't clear to me—there were knowledge gaps.

What I did in that exam was I took the entire three and a half hours to write the 50-mark question. I knew in my mind that I would just see how much I got in that 50 in my result. I knew from the moment I was writing that I would fail, because 50 is the passing mark and I couldn't get 50 out of 50, so I would fail. But very calmly, very methodically, in my exam hall—because I was used to going to the hall so many times—I sat down and finished the one question 100%, with neat clarity and full focus. I remember I got 33 or 34 out of those 50 marks. That gave me confidence for next time—I thought, "If I write properly and I got 30+ in one question, then with two questions I can do it."

That was something I did. I don't share this story openly on any platform because it's not an ideal approach. It's just something I did myself. I think only my wife knows it. I was very focused, very stubborn and persistent, and I ended up passing that exam, alhamdulillah, after three years.

Ruhul: So you started working at Acnabin and continued your part-time teaching profession. What happened after that?

Gazi Jishan: By 2016, I got a job offer—I interviewed for an internal audit role at BRAC. Everyone around me suggested not to join for two reasons: One, because it's an NGO, not-for-profit, and not a thriving, desired industry. Number two, it was internal audit, and nobody likes an internal audit career—everyone wants to be a CFO.

But for me, I took that chance. Since nobody wanted to go into internal audit and nobody wanted to go for not-for-profit, I wanted to take advantage of that. I took the job, and three years of working at BRAC was a very rewarding career because that actually led me to come to Qatar—through my internal auditing journey.

I was so passionate, focused, and devoted to internal audit that I tried to bring global knowledge and practices into my workplace in Bangladesh. BRAC was an amazing workplace that allowed me to do that. I experienced excellent growth in those three years, and I also got lots of highlights and spotlights across the globe.

For example, in 2018, I was recognized as an emerging leader by the Institute of Internal Auditors Global in their magazine, which is the global body of professional internal auditors that sets standards. They recognized 30 internal auditors under the age of 30 and I was featured as one of them.

I was the first Bangladeshi to be featured, the first South Asian even to go into their global newsletter. It was a big achievement for me. This was 2018, and soon after, I got headhunted for Qatar as an audit manager for a multi-billion dollar conglomerate family business. I joined here in 2019. I'll stop here—if you ask me questions, I'll go in that direction.

Ruhul: What happened after that? Let's talk about that journey.

Gazi Jishan: While I was still at BRAC in 2018, my business had already started. Qormotho wasn't called Qormotho at that time—we started as a business project between me and my partners, working on UK accounting work.

My life was always about doing two things: I was a student plus a teacher, then I was a teacher plus an accounting staff, then I was doing a job plus consultancy, and then I was doing a job and business. I always had a minimum of two hats on. Always.

In my entire career, only in the last four months have I worn one hat—nothing extra other than my business.

In 2018, I started my business journey with two of my partners. This was a small project where we worked on UK accounting clients in an outsourcing setting. It continued well and had demand, and I was skilled enough to make an impact in that setting. I was like a remote working staff member for a UK accounting firm. Meanwhile, I was carrying on my internal auditing career and moved to Qatar with a bit of doubt about my business continuity.

We had, by the end of 2018, three staff members. By the end of 2019, we had seven or eight. By the end of 2020, it grew to 14. By the end of 2021, it was between 22 and 23. End of 2023, it was 33. End of 2024, we were 55. It was up and down during the years, but we always elevated and responded to the demand of the outsourcing business.

All the while, I was also trying to achieve and accomplish success in my employment. I was focused on my job, coming to a new country, moving with a family—I had lots of challenges working full-time in a global company with advanced technology, multiple stakeholders, and different regulations.

I had to add value to the company and make sure I met the standards because I came as an internal audit manager managing seven internal auditors from different countries—Philippines, Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan. It was a mixed team, and all of that had to work together. Alhamdulillah, everything was going well until COVID happened and my boss resigned.

Things became ten times more difficult for me to perform. My boss resigned, and I was left alone with no guidance. COVID hit, everyone was working from home, and I was in a big mess in 2020.

Our business also took a hit as many clients cancelled their contracts. By April 2020, business was essentially gone.

Ruhul: That was another big turmoil point for you, personally and professionally. What happened after that? How did you turn things around?

Gazi Jishan: About my workplace, I had to be very focused on building relationships. Auditing is a tough job to get support and add value to the business because I had to work with the owners, the board, senior professionals, and it was a multi-diversified business. I had to understand the business, understand the controls, understand the risk, and then present them in the most suitable way. I had to bring together lots of skill sets, lead the team, lead the people.

On the business side, we were opportunistic and optimistic that something would happen. What we did was we didn't close down the business. We retained a few staff members, though we had to let go of most of them. I remember in April 2020, we had to give them three months' salary as compensation and termination letters because we didn't have enough projects for them.

Before the end of the month, we received another client's email saying they needed five team members. So we let go of five team members early in the month, and we needed five team members by the end of the month—which was, alhamdulillah, something we weren't planning for. We got it through a referral, and that was the rebuilding of the team.

From that point on, 2020 onwards, it was about quality service, clients referring to other clients, clients referring to other prospects. I used to receive emails occasionally in my inbox saying "we need help" because the world was also struggling with staffing problems. We were a solution provider at a reasonable cost with quality resources and good communication skills. We built the business around that model, and alhamdulillah, it helped us. We sort of restarted and re-engineered what happened during the COVID period.

Ruhul: I think we can continue the story up until the point you left the job—basically four months ago you left the job, right? So let's go until that point and then we'll go into the Qormotho story.

Gazi Jishan: Great. In terms of my five years with Qatar headquartered conglomerate, it was a lot of exposure and experience working with senior professionals in the profession and industry. I was continuously evolving the function and credibility of the internal audit function. I was willing to work differently—I was putting technology at the forefront, finding innovative ways to add value, building the team, empowering them in different ways.

For example, we used audit software, data analytics software, and project management software to get work done in the most suitable way because we had 4,000 employees and 25+ verticals to audit in Qatar, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and more. To achieve that, we used technology. Not everyone was technology-oriented, so I used to find the right matches—I assigned one team member to the project management software, another team member to the data analytics software, and that person became the trainer or focal contact for the rest of the team. In the previous approach, there was an attempt to train everybody on the same software, but that didn't help because everyone has different personalities and skill sets.

One auditor in the team was very smart and sharp—when he went into a warehouse or shop, he would quickly spot weaknesses because his observation skills and technical smartness were spot-on. Another auditor was very bold, outspoken, and had good presentation skills. Another auditor was very analytical but couldn't speak well in front of an audience, but could do a lot of analytical work on the computer. I used to pick those skill sets and utilize them as a group.

A lot of things happened, and every year we elevated our auditing department's image to the point where we did Internal Audit Awareness Month. This was a month in May where we used to go to stakeholders and preach to them, telling them the benefits and value of the audit department—because nobody likes audit, nobody likes to be audited. It was always difficult to maintain rapport, but we found different ways of facilitating seminars, sharing knowledge, doing quiz contests, rewarding the best audit-compliance departments, giving them certificates, recognizing them, and sharing platforms of knowledge together. We built strong relationships between audit and different departments, audit and business leaders.

This happened every year—we elevated our standards. The first year, we did just simple virtual awareness sessions. 2021-2022, we did internal team building. 2023, we did it with stakeholders. 2024, we did it with the group heads of the business, including the owners. I was promoted in my career during those years to Head of Internal Audit, and that's how I ended my period there.

Many stories within that, but in summary, I'd say that my opportunity and work in internal audit also upskilled me to work with a board, how to manage, how to develop and deliver strategy, how successful businesses operate, and I learned all those things which I carry with me. I'm trying to give that leadership back to my own company now.

Ruhul: That's an excellent story. I have two questions. One is about your experience and journey building a successful career in internal audit. You spent time in the UK education-wise, worked in multiple organizations in Bangladesh, and then worked in Qatar. If you could share a couple of reflections and lessons from this journey, particularly focusing on building a global career in accounting—what does it take to build a successful career in accounting? The second question would be: How did you make the decision to quit and go full-time into entrepreneurship? Although you started your entrepreneurial journey back in 2018 when you started Qormotho, doing it on the side versus doing it full-time are two different decisions. When you finally decided to go full-time—because it's a huge risk, and I would think you had a much more comfortable and secure lifestyle with your job relative to running a company—considering all of that, how did you make that decision to jump in?

Gazi Jishan: Can I start with the second question first?

Ruhul: Sure, please go ahead.

Gazi Jishan: To give you the entire truth and just to share with you—yes, it was not comfortable territory that I was moving into. But I am a believer in growth. I have witnessed growth in my personal and professional life and I enjoy growth. Growth happens in the discomfort zone as research suggests.

I left my job when I had a seven-figure salary in Bangladeshi currency, and leaving that job was just nonsensical to my friends, colleagues, and everyone else.

So how did I make up my mind?

Four or five things went through my mind. One of them being that I have to be a believer of my own vision, and I have to walk the talk. I cannot just have a business on the side and expect 50 or more employees to work towards a dream that I preach when I'm not believing in it myself. So I felt accountable to myself that I need to service this company that has grown organically over the years.

Second, I feel there's a lot of opportunity out there to grab, and being an entrepreneur, I can only grab those opportunities when I have time and energy to spend on them.

Third, and parallel to this, is that time is my biggest asset, and wherever I give time, it will become valuable. That's what I have learned over the years. Wherever I gave time and energy, I could build value there. So that's my confidence telling me—when I was new to internal audit, I was fresh, I didn't know in-depth, but as I gave time, when I focused on it, I learned more, I made connections, I practiced it, I could achieve what many internal auditors would find very valuable and very useful. So I felt if I give time to this enterprise, I can add value to this model and this business as well.

My accountability, my passion—I was feeling a lot of drive and passion for my business rather than my employment. For example, I started to lose my deep passion to contribute towards my workplace, rather all my energy started to be funnelling to my business initiatives. When I used to do a small task for my business—like interviewing, preparing a job description, writing or collaborating on a partnership, or having a meeting for a small project—I used to feel excited. I would spend hours on this happily without feeling any tiredness.

So I think to avoid that burnout and to give that passion my response, I took this call. But I didn't do it alone—I checked with my mentors. Throughout my life, I've always kept good connections with mentors.

I had phone calls with each of them: "This is what I want to do. This is what I'm deciding on. I'm almost decided; I just need you to tell me what you feel." All three of them said, "Yes, go for it. Go for it. Go for it."

I think that was pretty much in summary what happened in the last six months.

Ruhul: I think we can tackle the first question at the end of the conversation. We did a pretty long story on Qormotho in 2022. But for our readers of this interview, could you give them a recap of Qormotho's background story? What Qormotho is, what you do, and a little bit of the journey of how you started and evolved over time—the services that you provide.

Gazi Jishan: So Qormotho is an outsourcing BPO company that was born in Dhaka with three partners, including me. We co-founded Qormotho, and by the time the concept came to us, we were doing finance and accounting outsourcing—that was our first pillar of services.

Finance and accounting outsourcing has become very popular for remote working over the years with technology and cloud-based solutions. For example, you need accounting knowledge, you need to know the software—the popular software which the client uses or we can supply—and you need to be proficient in English communication and have business understanding. These are all available in Bangladesh with our accounting resources.

Many graduates, part-time students, or ongoing students are capable of serving that role with equivalent skills that a UK company is looking for, or an Australian company will work with, or a USA or Canadian company will work with.

So the demand in the western world is there. We put that into the business model of matching the supply and the demand. The value-added role that Qormotho plays is training and preparing the staff members for those responsibilities, supplying them resources, and upskilling them more and more. By the time any employee joins Qormotho, within one and a half years or even six months, you will notice a very significant transformation. They are working day-to-day with a foreign client, interacting with them, dealing with their books of accounts, and so forth.

Beyond that, Qormotho also does operations outsourcing and IT outsourcing services. Those are diversified business models that have also come along the way. We do customer support, virtual administration, and IT projects such as with AI. Similar to customer support business, we manage customer onboarding, query handling, inbox management, CRM, and dealing with clients of our front-end clients. So we're like a back-office support function.

We had only one client in the first year. We had three clients by the end of the second year and we kept growing after that.

Our staff members from the very beginning were very devoted, giving high quality service, professionally equipped, and also providing very innovative solutions. Those are our three value pillars.

As Qormotho was born, the name Qormotho came from a brainstorming session between us founders because we wanted to represent Bangladesh to the global world. We decided we would use one Bangladeshi word instead of going with "tech" or "BPO" or some savvy term—we went with a Bangla word. The term represents our attributes or core value of being hardworking. That's what we try to accomplish: by having a hard working attitude at the workplace, you could achieve almost anything.

As the sayings go: "an idiot with a plan will be better than a genius without a plan," or "hard work actually—the only difference between being successful and being unsuccessful is just passion, grit, and hard work." We built our company's values around that hardworking concept.

Alhamdulillah, we have hired locally—young graduates or students who are yet to graduate—and our workforce is a relatively young workforce. Now, as I mentioned the numbers of Qormotho employees before, alhamdulillah, we have grown from the UK as the main client base to multiple countries. We've worked with clients from Ireland, Canada, Australia and the USA.

Ruhul: You mentioned you started with accounting and finance and then eventually expanded to operations and IT in terms of services you're offering. Could you talk a little bit more about those services, what you offer in these areas? And the second question is: how does the operation work in terms of marketing and distribution? How do clients find you or come to you? How do you deliver services? Another aspect is that three of your co-founders are living in three different countries—how do you coordinate the operation? Are there any challenges because you live in three different countries? What are the upsides of that?

Gazi Jishan: I think I'll answer the second question first because it's coming to mind, and it's easy and straightforward. But this operational question—as you mentioned, it's a challenging setting.

The first thing that we had to master is that every staff member is remote working. The mastery of remote working is something necessary for building, scaling, or running a firm like ours. As you rightly pointed out, even the founders or directors are remotely placed. There's an inbuilt trust—also proven trust. It's not a trust that is on paper only, like a contract and service partnership agreement. It's a proven trust.

This is something we have to be very precise about, and we build trust amongst each other and allow space for each other to operate.

The other bit is we are using a lot of technology in our operations. For communication, we use Slack and WhatsApp. For our company wiki or company hub, we use Notion. For video recording or recording content on our knowledge hub, we use Loom. For my meetings and internal meetings as well, we use Fathom AI notetaker. I use Calendly for my marketing approach and internal meetings. We share calendars. We have software embedded into our day-to-day operations, and we are very mindful about using those software in the best way to keep our operations smooth and efficient.

We use AI a lot. A lot of AI is being used—for example, for marketing, resource development, training and social media content creation. We are using AI nowadays more and more.

Your question was around how do we operate as a business being in different countries—that's one aspect. This will continue if I want to talk about the team as well. The team is also very—when we hire a new person, we make sure we have a good orientation and integration process so that any staff member who is doing outsourcing for the first time in a different time zone, different country, where communication is on messages and there's no physical interaction, gets quickly oriented. Within a couple of weeks, the staff members get integrated into the process.

I think that's pretty much it. The operational managers have also played a big role in making sure the culture and messages pass along transparently and nicely. We have an open and transparent working relationship.

The best approach that I benefit from is delegate and hold them accountable, but delegate the work. Trust with accountability. I cannot see their work day-to-day. I cannot check on their attendance, their active/inactive status, whether they're idle, and I don't want to do that. My objective, my role, or my approach has been—if there's an accountability ladder that I learned—you're first accountable to your client, then you're accountable to your team members. If your client is happy and your team members are happy with the way you're doing it, then you're accountable to me, and I will be happy.

I don't have to do anything extra; I don't have to worry about where you work, how much you worked, did you work for eight hours or not. All those traditional workplace attitudes don't exist in Qormotho, with some high level policies put in place. It is not fully unregulated.

You can say very high-level, few rules, but very high-level rules. It's something that we apply. We don't apply many small, small rules to create boundaries or make it difficult for them to operate. We have very high-level requirements and expectations but very few of them, and the team members have adopted it very nicely.

Ruhul: That's beautifully put and covers a lot of the aspects of your operations. I want to extend that a little bit. You have built a quite successful outsourcing company in a space which is not really that common—accounting and finance outsourcing is not an everyday thing, right? It makes sense for a lot of companies, but still, in your space, what does it take to do it? If you want to give a checklist of, say, these are the five things you have to master if you want to do something like this.

Gazi Jishan: I think one very unique thing that we carry is understanding both worlds—understanding both parts of the opportunity. There are people who have a lot of money to invest, and they invested in Bangladesh and built high-caliber or highly technically proficient setups, but a few years down the line they were unsuccessful because the gap was they did not understand the resource and how to manage the resource or build on the capacity. So only investment will not help you; only connections will not help you.

One side of it is to understand the demand and understand the cultural differences and be the matchmaker for that. It is very important. I'm Bangladesh-born, brought up, grown, taught students, over the years have earned my credibility.

Number two is vision. Having that vision is mandatory. When we started, we always talked global—"We will go global"—without knowing or having that sort of setup. That vision can sound too ambitious, but it showcases you are hungry for more.

The next bit that comes hand in hand is: once you have that vision, you have to be consistent in your approach, and you have to be consistently delivering or building that vision, taking every task seriously, not losing an opportunity, not taking any opportunity to fall through the cracks..

We have a CRM software ourselves where we have a list of all the contacts we work with—current, past, prospect—everything is built there. Social media is active; you can always have connectivity. No shyness here, because one thing I learned is that international organizations are seeking out a solution provider for solving their problem in hand and we have a solution to offer. Companies don't pay us for nothing—they pay because we are offering a solution. So there's no hesitation in contacting them, telling them, "If you need me, I'm available." That sort of marketing approach, keeping the bond, is very important.

Now, I think a big question will be: how do you start? How do you find your first client? How did you find your first client? Well, there is no one path. It could be from a freelancing website, freelancing marketplace where you started working with a contact and you can build that and build your own image and go outside and start your own service delivery. It could be from a contact you know who is in the front market—for example, US or UK—who refers to you.

I think some of the blueprints could be what I mentioned here: how it starts, how it can grow, how it can be maintained, and having that mindset and skill set of working in different time zones. You have to be adaptive to those cultures because particularly when clients are looking for the right attitude. You can be the best accountant, but you may not have any job in an outsourcing setting because of attitude.

One thing I preach to professional accountants, my fellow members of accounting professionals, is having the right attitude. Sometimes we as accountants maintain a reserved mindset: "I'm a chartered accountant; I cannot go wrong. I am the boss, and I understand everything." Well, it's okay—you can have all that knowledge, you can still be humble, you can still serve the customer, you can still be humble and down-to-earth and friendly and have a frank conversation.

Sometimes those attitude problems—a Bangladeshi chartered accountant who struggled all his life to become a qualified accountant, I understand it takes a lot of grit to achieve that—but I think you need to reduce that sort of voltage. This attitude makes a lot of difference in the client's eyes.

Ruhul: That's beautifully put. I want to ask two more questions in this line. Since you look after marketing, sales, and partnerships, and you mentioned some very useful ideas around marketing and communication, do you have any checklist in terms of, say, these are the five or ten things one should consider in terms of marketing and sales when you're dealing with international clients?

Gazi Jishan: Yes, I do have—when I went into business, my first priority was skills development, and I am personally investing on my own training. I'm part of a coaching group. What am I learning? I'm not learning accounting standards, I'm not learning auditing. I'm learning marketing and business development.

One of the models that I am focusing on is positioning. Positioning your business to become a specialist. Specialist in a particular area. You choose your specialization, but you have to sound and look like a specialist, serve your client with specialist skill sets.

Everybody would like to go to a specialist surgeon instead of a general medicine doctor. Why? Because they believe that they will get better treatment. So you have to choose your industry specialization, or your service specialization, or even your stage of client that you serve specialization. It can be anything. It can be you're a healthcare specialist, it could be you're a dental accountant for dental practices, it could be accounting for property business, it could be accounting for startups. But it has to be specialist.

In your example, you are a startup specialist, so you are focused on that. When you write that, everyone who is a startup will think, "Ah, this is for me." That's why you will attract traction. In my marketing approach, I would suggest this, and I would tell anyone to do this—it's working for us and it will work for anybody. Become a specialist in whatever you choose, and then be consistent on that.

The second approach that I am focusing on is something called farming as opposed to hunting. Farming is building that field, building authority in a particular space, making it ready for future growth and plantation. Hunting is an approach where you target and you send cold emails, you send direct messages, you send connection requests, cold calls—all those marketing tactics are more of a hunting approach. I prefer, and I'm going through, that farming approach, and it does not yield immediate results, but hopefully, there is a long-term result to that.

Our website also helps us to get inquiries from prospective clients. LinkedIn is a useful platform where decision-makers and my prospect finance people and business contacts are hanging around. As a marketer would say, you need to figure out where your clients are lurking around and target your marketing tactics in those directions. So I am using LinkedIn

Ruhul: These are some very useful ideas. I'm digging deeper into this segment of questions. Here's another one I'd like you to demystify: You've built what I'd call a quite successful business in a short period. This is in a market we're not really known for—accounting and finance outsourcing services. But you've built a successful business out of it. A 55-person team is no joke, and three-country offices are big milestones. If you could demystify the growth, what contributed to it? You've built a wonderful culture—people are passionate about their work, they take ownership, show honesty, deliver high-quality work, and work hard. Those things have contributed. But tactically, focusing on the growth hacking aspects for Qormotho, what are five or six things that contributed to your growth?

Gazi Jishan: One powerful hack is task organizing and delegation. I didn't keep any work or client communication restricted. I kept it open with the team. When I delegated, the team member would immediately delegate further down the order, and delegation would happen at the right level.

This freed up my time to focus on new business or the next step. I'm only involved when a prospect comes to my sales call and we get the contract signed. After that, I don't get involved day-to-day unless they need me. I spend time “working on the business” rather than “working in the business”.

The second part is making sure the team doesn't feel unsupported. Every time they were in trouble or difficulty, especially my direct reports, I would make myself available and address the issue together. So it goes both ways—I take a hands-off approach but remain available for support. Empowering team members with the right accountability goes a long way.

What happened is the team became more capable than me at getting new business from existing clients. One of our growth strategies is getting new clients. The other growth is driven by client extension. The team did it so well that from one resource, they started working towards building the need for more resources. Then they'd come back and say, "The finance director is asking for another staff member to support another area," or "The head of marketing is asking for support—another person." So we grow within the client, and we grow as an organization.

Regardless of all the technical skills, high-quality output needs to be taken into account. That means our hiring and training of staff members, making sure we only hire the best from the pool. That's something we've always taken care of.

I think all combined, it worked well. We ended up having more orders, long-term relationships, and as I mentioned, client referrals contributed to growth.

Ruhul: That's wonderful. Coming back to Qormotho, what are the goals going forward? What are the short-term and long-term plans? Since all three founders have now moved full-time, the stakes are much higher, so ambitions should be bigger as well. What are the plans for the next three to four years, and also 10 to 15 years?

Gazi Jishan: In the short term—as our priority—we'd like to bring Bangladesh to the forefront of accounting and finance outsourcing.

Let me give you an example. Two months back, I was at an ACCA Bangladesh conference where I was the keynote presenter on finance and accounting outsourcing. The panel discussed that we have a lot of supply and setups tested for customer support, graphics outsourcing, imaging outsourcing, and IT outsourcing. It's tested, and Bangladesh is well-known for software outsourcing. But finance and accounting is a high-priced, premium, lucrative market—and we're not popular in that space.

So one objective of Qormotho is to promote Bangladesh as the finance outsourcing destination for the world. We're continuously doing that. One of my clients, a UK Chartered Accountant, commented, "You're the first Bangladeshi company to offer us accounting services that I've come across, because I can't find any. There are lots of Sri Lankan companies, Filipino companies and individuals, Indians and Pakistanis—they're the most common providers in this field."

We want to make that unique proposition and take advantage of being the first mover, inshallah. That's on our radar. Then we want to build the business with multifold growth. We reached 50 staff members last September, alhamdulillah, and we just want to grow from here—make it two-fold, three-fold as we continue.

We put financial targets in our annual calendar now. Whatever was a dream, we converted into a goal, then into a target, then into numbers. So now we have more clarity about what we want to achieve step by step. Those systems weren't there before. We have strategy; we have documented things now that were absent before.

In general, as a business looking to become successful, one more thing I want to personally achieve—using the platform and success story of Qormotho—is something I wish to serve the community with: helping accountants and auditors of Bangladesh become successful globally.

Ruhul: You've worked across countries and organizations, and now you're building your own company. If you compile your journey and experience, what are some lessons you've learned in terms of building organizations, running organizations, and becoming a successful professional?

Gazi Jishan: I think the first thing about professionalism is what I call being relevant. Relevance really matters. When I was in accounting, I was only consuming knowledge and networking with relevant people—meaning the accounting industry. I wasn't looking at everything the world has to offer. The world has so much to offer; information is at our fingertips. But if you spend time everywhere, your mind has limited capacity.

When I moved to audit, I made relevant connections with audit professionals where I could benefit from like-minded professionals. Being relevant is my strength, and I practice it today in my entrepreneurship journey. I'm making connections and talking to people in the entrepreneurship space. I'm no longer going back to accounting or auditing—not that those are small and this is big, it's just my relevance.

The second thing is being authentic—being truthful, being genuine. When I'm a business owner or people leader, this is my biggest strength. For example, when I took the auditing job and came to Qatar, there were many engagements where I wasn't fully skilled to tackle the entire assignment myself. I sought help, without the fear of being judged. I was very frank and honest.

In your employment, even in your real life, instead of pretending and trying to make a good picture, just be authentic. Problems will be there in life—deal with them as problems. Don't try to avoid or ignore them. When your staff members see that you're open, transparent, authentic, and caring, they'll respond with the same attitude. They'll be caring toward your organization and transparent with you.

I have many cases where staff members come to me directly, skipping line managers one or two levels, to tell me something in confidence. They feel that if they talk to me and share a concern, I'll give them an objective opinion despite being the company's boss.

The third thing would be listening skills. Listening skills are overlooked, but they're so powerful. Listen to your clients. Listen to your staff members. Listen to your partners. Just listen. In this race, everyone wants to speak. Everyone has something to say, something to share. I actively listen, and it's something I continuously nurture. I want to listen, respond to that, and try to understand. Those are the real-life takeaways from my journey.

Ruhul: That's beautifully put. The authenticity piece really resonates—if you don't know something, asking the "stupid question" is the ultimate way to learn.

Gazi Jishan: Exactly—ask like a child would ask. Be a child. In internal audit, my career revolved around asking questions. I learned a lot, and my profession shaped me as a person. As an internal auditor, we're trained to ask the right questions. Be curious like a child. Don't assume —ask, and get the facts out.

Ruhul: Any parting thoughts as we wrap up?

Gazi Jishan: I think we captured what I wanted to share through your questions. One thing that comes to mind as a parting thought is about business partnerships—it's another sensitive area you need to be very careful about.

In our approach, we always prioritize the other partner more than ourselves, even if we have to. We have a very consultative and open relationship. Although we don't come from the same background, family, or mindset—I may have a different lifestyle from my partner—when it comes to business, if you can apply the mindset of having zero expectations from anybody, zero complaints, then things will sustain, inshallah.

These are all teachings from our beautiful religion, Islam, that you can actually apply to become successful. You don't have to go anywhere else.

Ruhul: This is particularly important for Qormotho because you have three partners living in three different countries, in three different cultures. That must make communication challenging.

Gazi Jishan: Exactly.

Ruhul: But the point you mentioned applies not only to partnerships but to personal relationships and all kinds of relationships. When you have that mindset—"I'll give more and I won't be an accountant in this relationship, always taking notes of what I gave and what I didn't receive"—you're not guarding your losses. That's a really beautiful attitude to have. Thank you so much for being generous with your ideas and insights. This has been an enlightening conversation for me.

Gazi Jishan: Thank you for speaking with me. I thoroughly enjoyed the conversation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.